What Do Unreasonable Corporate Profits Tell Us About Our Economy?

How "crony" is Canada's version of "capitalism"?

Crony capitalism is a corrupted version of market capitalism where, instead of competitive markets delivering true value to consumers, powerful businesses invest in extensive lobbying and influence-peddling efforts to stack the deck. The goal is to extract from governments favorable selective subsidies, protective tariffs, and regulatory barriers. As a rule, you’re more likely to encounter the features of crony capitalism where governments wield substantial authority over resource allocation.

You won’t find any single economic indicator that’ll clearly scream “cronies be here!” But there are certainly metrics that can suggest troubling trends. To get some sense of the current shape of Canada’s business market, I thought I’d explore some easily-available data resources.

Income disparity in Canada

One useful indicator might be income disparity. In other words, the ultimate goal of crony capitalism is to concentrate wealth in the hands of cronies, rather than the general population. So you’d expect to see poorly distributed wealth.

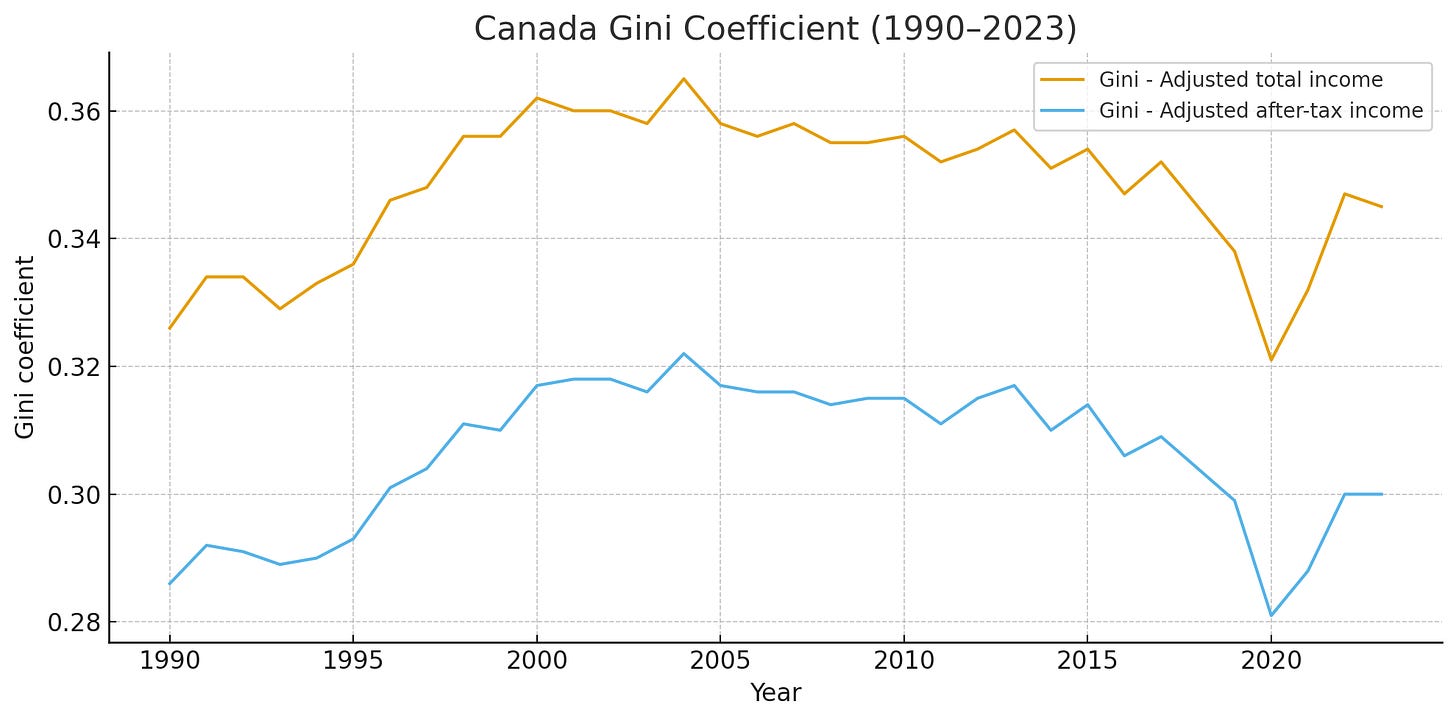

The Gini Coefficient is a pretty good tool for measuring income disparity. A score of “one” would indicate all income flows to a single person, while “zero” would indicate that all wealth is shared equally by everyone. Shifts in Gini values over time can suggest developing trends. Here, based on Statistics Canada data, is what that looks like in Canada:

“Adjusted total income” represents all income, including government support programs. “Adjusted after-tax income” is what Canadians actually take home after taxes are deducted from their income. Once our actual spendable income is calculated, the wealthiest and poorest among us are much closer together.

But even if we use the higher “total income” measure - and ignore the COVID disruption - it’s clear that income disparity in Canada has been falling since the early 2000’s. In fact, our Gini values are lower than the OECD average, and far below much larger countries like China and the U.S.

So if that’s where we chose to finish our research, we’d happily conclude that there’s precious little crony capitalism going on here.

The end.

Not so fast. The Gini coefficient is an important number, but it’s far from the whole story.

Other economic indicators

Another indicator of cronyism is stagnant productivity growth, suggesting widespread misallocation of capital. Of course, many factors can cause stagnation, but the dominance of a few inefficient and connected businesses can produce zombie companies that drag productivity down.

Canada has certainly been rich in stagnation lately. Multifactor productivity growth of less than one percent annually for more than a decade is not a good thing. Canada’s recent growth has been…well, it hasn’t been at all. Our average “business sector1” growth has been slowing - measuring negative 0.10 percent - in the years since 2015.

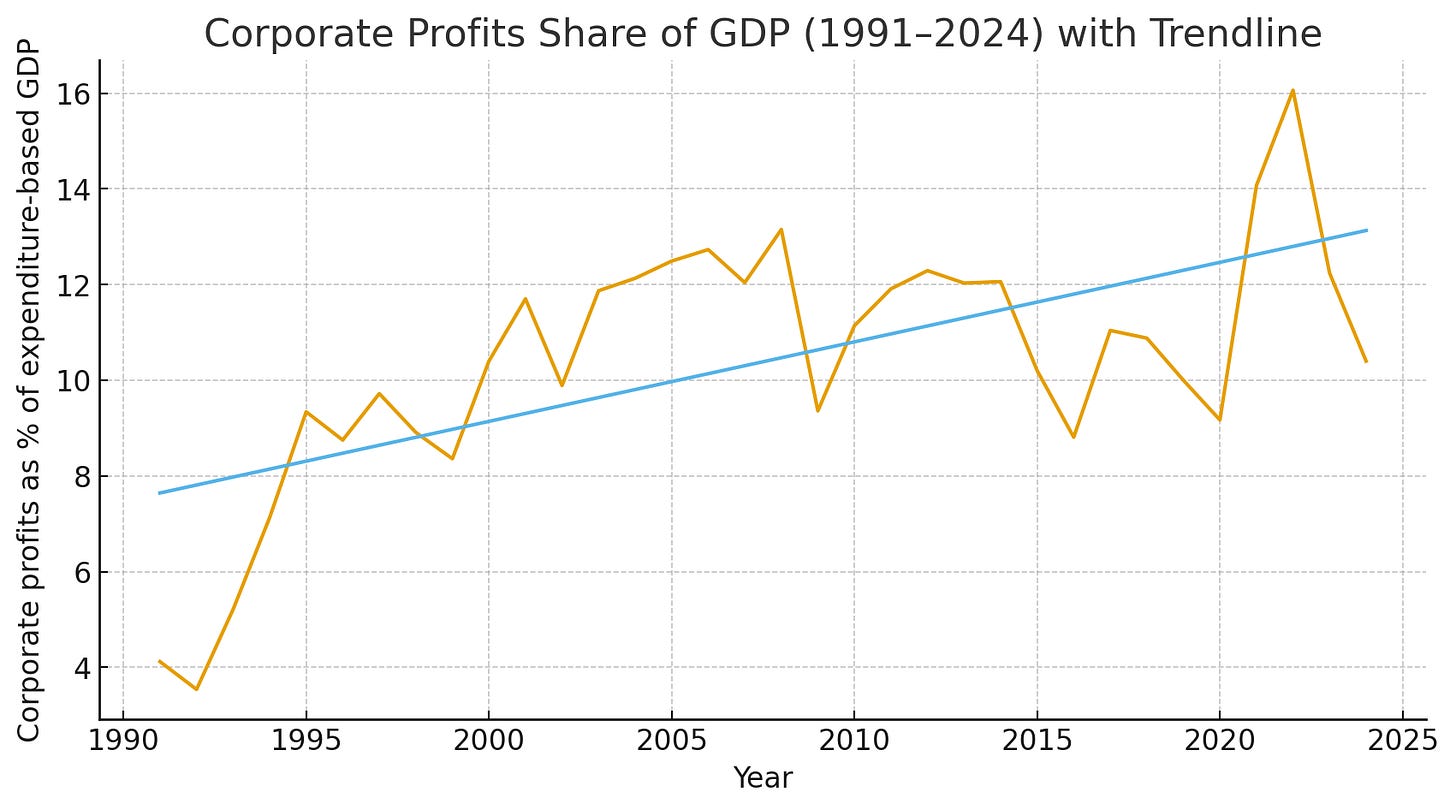

We should also look at corporate profits. Specifically, the corporate profits’ share of total gross domestic product (GDP). As you can see from the next graph, when I measure “corporate profits before taxes” with the gross domestic product (expenditure-based), things have been looking very good for corporations.

Of course, if those annual shares of GDP had been accompanied by similar growth in the labor income share of GDP, then it wouldn’t necessarily be a cause for concern. However, with the exception of the COVID years, the labor income share has been dropping modestly since 2014.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into those corporate profits numbers. The sharp declines in 2001, 2009, 2015–2016, and 2020 align with (respectively): the dot-com slowdown, the global financial crisis, the oil price collapse of 2014–2016, and the COVID recession. All of which reflects the sensitivity of Canada’s corporate sector to global demand shocks.

But that post-2020 surge is historically unprecedented. Canada saw an unusually profit-heavy recovery where firms, particularly in resource sectors, captured a large share of national income. There were record margins in energy, finance, and real estate; supply-chain bottlenecks that allowed firms to raise prices faster than costs; commodity price spikes (after the global reopening); and some wage suppression due to limited labor bargaining power.

Even if those post-COVID profits were temporary, the numbers still suggest that corporate bottom lines are well above historical norms. That, along with the stagnation we’ve already mentioned, does suggest we might be on the wrong side of the “crony-continuum” - and moving further in the wrong direction.

As a rule, other related areas of concern can include:

Large and persistent government subsidies or bailouts to specific industries. Broadcast media companies immediately come to mind.

High levels of perceived corruption and weak rule of law. Canada is nowhere near true banana-republic levels here, but we’re not exactly squeaky clean, either.

Inflated public procurement costs and infrastructure overruns.

What should governments be doing about all this?

Enhance competition policies and reduce regulatory barriers

(Actually) eliminate interprovincial trade barriers

Police telecom/banking/grocery mergers more closely

Force regular reviews of all regulatory frameworks

Reform subsidy and bailout frameworks

Audit and reassess harmful and disruptive subsidies for industries like the media

Support genuine innovation

Improve procurement and infrastructure governance

Use outcome-based contracting with penalties for overruns, plus public dashboards tracking costs in real-time

Interested in some related reading?

So How's That Economy Doing?

Just a quick warning: this post will be quite a bit more technical and geek-y than usual. But I think it’ll help shine some light on how economic indicators can sometimes come a bit unstuck from street-level realities. And that, in turn, should change the ways we assess the real-world impacts of government policies.

The Problem of Corporate Tax Rates

Are Canadian corporations paying their share? Well, what is their share? And before we go there, just how much are Canadian corporations paying?

What Canada's Underground Economy Tells Us About Our Tax System

One way or another, we’ve all been exposed to the underground economy. Whether it’s sending your kids to a “cash only” home-based daycare business, buying produce at a “pop-up” roadside farmer’s market, or not reporting taxable income from a basement apartment rental.

“Business sector” covers the whole economy less public administration, non-profit institutions and the rental value of owner-occupied dwellings.”

Thank you for another interesting and informative post, David. A question though...

According to MacDonald-Laurier, government sucked up 64% of Canadian GDP in 2023. That is beyond apalling; it is truly frightening. Watching the current gov "run" the economy gives me no comfort at all.

It is my contention that the only significant difference between the US and Canadian economies is the rate of capital formation. Theirs is healthy and ours is absent. Looking at the size of gov (% of GDP) in both countries leads me to believe that taxation in Canada is preventing capital formation. Someone, anyone, please offer an example of a Canadian company that was started and grew without foreign investment and/or government cover.

And I can't understand how we could pretend to be a capitalist (free market) country if we prevent capital formation.

Could you find numbers that would support or refute that supposition, please?

Thank you, John

P.S. I have subscribed :-)