The Problem of Corporate Tax Rates

Why it's nearly impossible to avoid causing more harm than good

Are Canadian corporations paying their share? Well, what is their share? And before we go there, just how much are Canadian corporations paying?

According to Statistics Canada, in the second quarter of 2024 all levels of government received $221 billion from all tax revenues (excluding CPP and QPP). Of those, provincial governments took in $95 billion, and local (municipal) governments got $21 billion. Using those numbers, we can (loosely) estimate that all levels of government raise somewhere around $883 billion annually.

If you’re curious (and I know you are), that means taxes cost each man, woman, and child in Canada $21,544 each year. Trust me: I feel your pain.

Based on Statistics Canada data from 2022 (the latest comparable data available), we can also say that roughly ten percent of those total revenues come from corporate taxes at both the federal and provincial levels.

Keep that 10:90 corporate-to-personal tax revenue ratio in mind. Because what if raising the corporate tax rate by, say, five percent ends up driving businesses to lay off even one percent of workers? Sure, you’ll take in an extra $7 billion in corporate taxes, but you might well lose the $12 billion in personal income taxes those laid-off workers would have paid.

How Much Should Corporations Pay?

Ok. So how should we calculate a business’s fair share? Arguably, a single dollar’s worth of business activity is actually taxed over and over again:

When a corporation earns revenue, it’s taxed on its profits.

Any remaining profit may be distributed to shareholders in the form of dividends. Shareholders, of course, will pay income tax on those dividends.

Corporations pass on part of the tax burden to consumers through higher prices. When consumers pay those higher prices, a part of every dollar they spend is indirectly taxed through the corporation’s price adjustments.

Shareholders may eventually realize capital gains when they sell their shares. These gains are, naturally, also taxed.

I guess the ideal system would identify a corporate tax rate that takes all those layers into account to ensure that no single individual’s labor and contribution should carry an unreasonable burden. I’ll leave figuring out how to build such a system to smart people.

Does “Soaking Rich Corporations” Actually Work?

Do higher corporate taxes actually improve the lives of Canadians? Spoiler alert: it’s complicated.

Government policy choices generally come with consequences. From time to time, those will include actual solutions for serious problems. But they usually leave their mark in places of which lawmakers were initially barely aware existed.

Here’s where we get to explore some of those unintended consequences by comparing economic performance between provinces with varying corporate tax rates. Do higher rates discourage business investment leading to lower employment, economic activity, and incoming tax revenues? In other words, do tax rate increases always make financial sense?

To answer those questions, I compared each province’s large business tax rate with four economic measures:

Gross domestic product per capita

Business gross fixed capital formation (GFCF - the money businesses invest in capital improvements: the higher the GFCF, the more confidence businesses have in their long-term success)

My own composite economic index (see this post)

Using four measures rather than just one or two gives us many more data points which reduces the likelihood that we’re looking at random statistical relationships. Here are the current provincial corporate tax rates for large businesses:

If we find a significant negative correlation between, say, higher tax rates and outcomes for all four of those measures, then we’d have evidence that higher rates are likely to have a negative impact on the economy (and on the human beings who live within that economy). If, on the other hand, there’s a positive correlation, then it’s possible higher taxes are not harmful.

When I ran the numbers, I found that the GDP per capita has a strong negative correlation with higher tax rates (meaning, the higher the tax rate, the lower the GDP). GFCF per capita and the private sector employment rate both had moderately negative correlations with higher taxes, and my own composite economic index had a weak negative correlation. Those results, taken together, strongly suggest that higher corporate tax rates are indeed harmful for a province’s overall economic health.

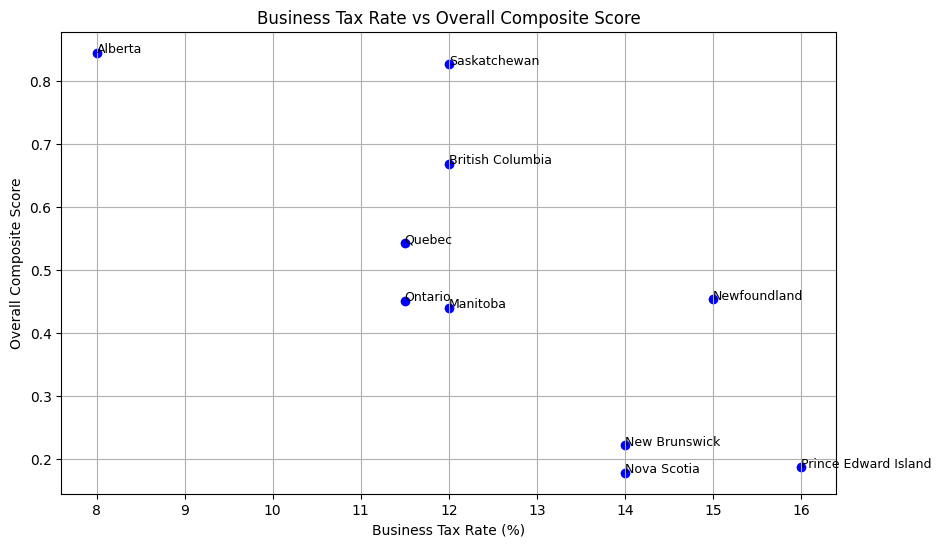

Here’s a scatter plot that illustrates the relationship between tax rates and the combined outcome scores:

Alberta, with the lowest tax rate also has the best outcomes. PEI, along with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, share the high-tax-poor-outcome corner.

I guess the bottom line coming out of all this is that the “rich corporations aren’t paying their share” claim isn’t at all simple. To be taken seriously, you’d need to account for:

The true second-order costs that higher corporate taxes can impose on consumers, investors, and workers.

The strong possibility that higher corporate taxes might cause more harm to economies than they’re worth.

The strong possibility that extra revenues might just end up being dumped into the general pool of toxic government waste.

Or, in other words, smart policy choices require good data.

Now available:

In the second paragraph, you describe revenue received as “income taxes”, but that amount includes all taxes, such as GST and payroll taxes, not just income taxes. You just need to delete the word “income”.

Otherwise, I suspect you need to control for a couple other variables. I suspect Alberta’s success on the measures you chose (and its choice of corporate tax rate) have as much to do with its high level of resource revenue compared to other provinces.

I’m not sure your numbers are correct. I think the federal gov takes in about $200billion bot quarterly in income taxes . Ontario takes in about $35b annually.