Is This What It'll Take to Solve the Housing Crisis?

I’ve written my fair share of articles focusing on Canada’s housing crisis. I’ve discussed the roles taxes, development fees, zoning restrictions, and expensive environmental policies have had on construction. And I’ve discussed the pressures ten years of out-of-control immigration placed on availability and affordability. I even took a look at ideas being kicked around internationally.

But I’ll be the first to admit that I haven’t identified any sure-thing, plug-and-play solutions. Solving just the supply problem or just the demand problem - or even both of them along with all those nasty government regulations and taxes - probably wouldn’t make all that much of a difference.

However, Toronto real estate analysis John Pasalis just published The Great Sell Off , a report on the state of housing in Canada. Since the report contains some ideas that I think bear amplifying, I thought I’d discuss them here.

Pasalis acknowledges that there are indeed significant supply-side problems like development fees and zoning restrictions. And there have also been significant demand-side issues, like our disastrous mass-immigration policies.

But addressing just those won’t solve our problem. And that, as Pasalis would have it, is largely because home ownership is no longer about a place to live and to store wealth for personal retirement. In Canada - more than most other countries - home ownership has also become a way to store wealth as an investment. Pasalis calls this the financialization of the housing market

Pasalis observes that real estate investors can outbid most Canadian families on single-family homes because they have easy access to low-cost capital and - critically - no pressing need to limit their spending to a low multiple of the median household income. That means there’s no effective market constraint on housing prices.

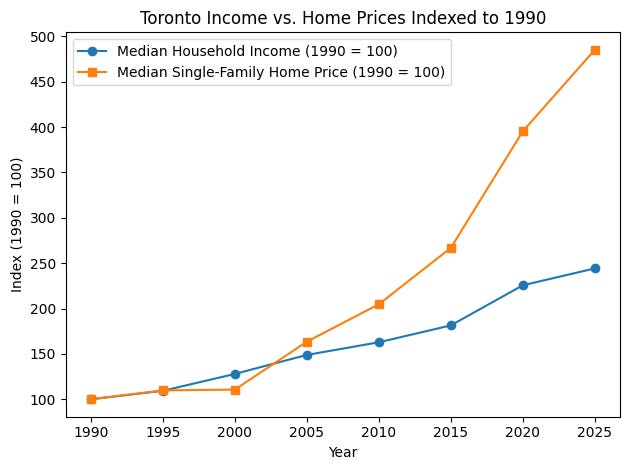

Not only do the business models used by investors depend on the steady increase in real estate market prices, but they also drive those increases. The growing disconnect between household income and housing prices over the past few decades gives us all proof we need:

So removing regulatory and capital constraints will never be enough because, to some degree, that would just add more fuel to the fire. But at the same time, it would be a disastrous mistake to legislate investors out of the market completely because that would undoubtedly cause far more harm than good.

The trick, as Pasalis sees it, involves carefully balancing government tax and housing policies. Besides reducing zoning restrictions and removing counter-productive policies, that would involve:

Increasing down payment minimums for anyone who’s not a first-time home buyer from 20 percent to, say, 35 percent

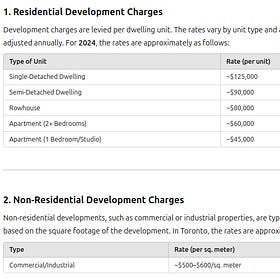

Lowering construction-related fees and land transfer taxes (likely in the form of a rebate) exclusively for construction that would be used for first-time home buyers

Restricting existing preferential capital gains tax treatment to a smaller subset of owners in order to level the playing field between investors and residents.

Enforcing measures like those would not be impractical or even disruptive. But they would organically price investors out of many deals, carving out more space in the market for families.

Perhaps the most immediate impact of such policies would be on investors: where will they spend all that capital that was, until now, sunk deeply in real estate? Well, why not redirect it to actual innovation and industry? Those are, after all, traditional destinations for investment capital.

In fact, as Pasalis observes, Canada’s dismal labor productivity rates in relation to the U.S. and other countries aren’t because we’re lazy. To a large degree, they’re the product of the fact that we don’t produce anything of value anymore: too much of our wealth comes through the appreciating value of our real estate.

Now for the fun part.

Assuming a stable population and flat nominal prices (something that more or less reflects real world conditions over the past six months or so), I asked an AI model for a stylized, back-of-the-envelope scenario model (not a forecast) for the Toronto market. Think of it as: “If these levers are pulled and nothing else moves, what order of magnitude effects are plausible over 10 years?”

The result of the thought-experiment was a 15-20 percent reduction in home prices over ten years. But that’ll come with some moderate economic and political blow back. My AI was particularly (and deliciously) cynical about the ability of governments at all levels to stay the course and not quietly self-sabotage.

Baseline setup (Year 0)

We need a simple reference household and home.

Assumptions

Median household income (real): $100,000

Median owner-occupied home price: $1,000,000

Mortgage rate: 5% nominal, stable

Amortization: 25 years

Baseline down payment: 20%

No real income growth

No population growth

No nominal price growth absent policy (prices flat)

Baseline affordability metrics

Price-to-income ratio: 10.0×

Mortgage principal: $800,000

Annual mortgage payment: ≈ $56,000

Payment-to-income ratio: 56% (clearly unaffordable by traditional standards)

This is intentionally “Toronto-like” but abstract.

Policy lever 1

Raise minimum down payment for non-first-time buyers from 20% → 35%

Mechanism

Reduces effective demand, especially leveraged investors and move-up buyers

No population growth means lost buyers are not replaced

In a flat-price environment, this creates persistent excess supply pressure

Quantitative assumption

Empirical literature on credit tightening suggests:

Sales volumes fall sharply

Prices drift downward slowly, not crash

Let’s assume:

–0.75% price pressure per year, cumulative

(very conservative — less than many macroprudential episodes)

10-year effect

1,000,000×(0.9925)10≈928,0001{,}000{,}000 \times (0.9925)^{10} \approx 928{,}0001,000,000×(0.9925)10≈928,000

📉 Price decline: –7.2%

Policy lever 2

Rebating development charges & land transfer taxes for first-time-buyer construction

Mechanism

Lowers per-unit cost of new entry-level homes

Improves project feasibility at lower price points

With stable population, new supply must displace prices elsewhere

Quantitative assumption

Let’s assume:

Targeted policy increases effective supply of entry-level units by 1% of stock per year

Not all of that translates into net new occupancy, so price impact is muted

Assume:

–0.6% annual price pressure, compounding

10-year effect

928,000×(0.994)10≈873,000928{,}000 \times (0.994)^{10} \approx 873{,}000928,000×(0.994)10≈873,000

📉 Additional price decline: –6.0%

Policy lever 3

Narrow preferential capital gains treatment for housing investors

Mechanism

Reduces post-tax return on housing as an asset

Encourages:

Fewer investor purchases

Some investor exits

In a no-growth market, this shifts the demand curve left permanently

Quantitative assumption

Empirical estimates tend to show small but persistent effects.

Assume:

–0.4% annual price pressure, compounding

10-year effect

873,000×(0.996)10≈839,000873{,}000 \times (0.996)^{10} \approx 839{,}000873,000×(0.996)10≈839,000

📉 Additional price decline: –3.9%

Combined 10-year outcome (all three policies)

Home price

Starting: $1,000,000

Ending: ≈ $840,000

📉 Total nominal decline: ~16%

What this does to affordability

New affordability metrics

Price-to-income ratio:

840,000/100,000=8.4×840{,}000 / 100{,}000 = 8.4×840,000/100,000=8.4×

Mortgage (20% down):

Principal = $672,000

Annual payment ≈ $47,000Payment-to-income ratio:

47% (still bad, but materially better)

If buyer is first-time (benefiting from policy #2)

Assume:

Rebates reduce effective purchase price another 5%

Net price ≈ $800,000

Mortgage ≈ $640,000

Annual payment ≈ $44,700

Payment-to-income: 44.7%

Why this result is actually large in policy terms

A 16% nominal price decline over a decade:

Is not a crash

Would barely register year-to-year

But dramatically changes long-run affordability

Historically:

Canadian housing policy typically moves prices by single-digit percentages

Sustained multi-lever pressure like this is rare

What this model is not capturing (important)

This is conservative because it ignores:

Wage growth (would improve affordability further)

Real interest rate declines

Behavioral feedback loops (expectations shifting)

Zoning reform multipliers

Immigration-driven demand (explicitly excluded)

It also ignores:

Political economy resistance

Transition effects (e.g., short-term construction slowdown)

Bottom line (plain English)

Under stable population and flat baseline prices, your three policies together plausibly produce:

~15–20% lower home prices over 10 years

Meaningfully improved affordability, especially for first-time buyers

No crash, no sudden shock — just sustained pressure

What about economic and political fallout from such a policy shift? Here’s what my AI offered:

1. Household balance-sheet stress (quiet but widespread)

What happens

Existing owners see home equity stagnate or erode

Recent buyers (last 3–5 years) experience paper losses

“Move-up” households are hit hardest: they lose equity and face higher down-payment hurdles

Why this matters

Housing wealth in Canada functions as:

Retirement security

Consumption collateral

Intergenerational transfer mechanism

A prolonged period of:

Flat or falling prices

Higher transaction frictions

→ leads to precautionary behaviour: less spending, fewer renovations, delayed retirement.

Scale of disruption

Macro impact: mild but persistent drag on consumption (think tenths of a percent of GDP annually)

Political impact: high — this hits middle-aged, voting-heavy homeowners

⚠️ Not a banking crisis — mortgages remain serviced — but a confidence shock.

2. Transaction freeze & labour mobility problems

What happens

Higher down-payment rules + lower price expectations → fewer transactions

Capital gains changes reduce incentive to sell investment properties

Owners become “locked in” waiting for better conditions

Consequences

Labour mobility declines:

Harder to move for work

Regional mismatches worsen

Family mobility suffers:

Downsizing delayed

Empty nesters stay put

New supply competes poorly with resale stock in the short term

Why this is a big deal

Canada already has low housing turnover by OECD standards.

This policy mix pushes it lower.

📉 Lower turnover means:

Less price discovery

Fewer listings

Paradoxically tight rental and ownership markets in some segments

3. Construction sector whiplash (even with rebates)

What happens

Even with targeted incentives:

Developers face lower expected exit prices

Financing becomes harder (lenders price in slower appreciation)

Marginal projects get shelved

Net effect

High-end and speculative construction slows sharply

Entry-level construction improves somewhat, but not enough to offset total decline

This creates:

Employment volatility in construction trades

Pressure on municipalities reliant on development charges

Political economy trap

Municipalities depend on:

Development fees

Land transfer taxes

Your policy explicitly reduces both — so cities may:

Resist implementation

Raise other fees or taxes to compensate

Quietly restrict permits

4. Rental market stress (counterintuitive but real)

What happens

Investor demand drops (intended)

Some small landlords exit

New rental construction slows (unintended)

With stable population:

Rental demand doesn’t explode

But rental supply tightens unevenly

Consequence

Rents may rise faster than prices fall, at least temporarily

Politically explosive if not anticipated

This is one of the classic housing reform failure modes:

“We fixed ownership affordability and broke rentals.”

Mitigation usually requires:

Parallel rental construction incentives

Or rent stabilization policies (which have their own risks)

5. Municipal fiscal stress

What happens

Over a decade:

Land transfer tax revenues decline

Development charge revenues fall

Property tax base grows more slowly

Toronto is especially exposed.

Responses cities are likely to take

Raise property tax rates

Increase user fees

Cut services

Quietly obstruct new development approvals

This is not hypothetical — it’s a known municipal reflex.

6. Political backlash & policy reversal risk

Who gets angry

Recent buyers

Small landlords

Construction unions

Municipal governments

Boomers relying on housing wealth

How it manifests

Media narratives of “destroying the middle class”

Court challenges (especially around tax changes)

Future governments rolling back or neutering the policies

This is the single biggest implementation risk.

Canada has a long history of:

Announcing housing reforms

Diluting them under pressure

Quietly reversing them later

7. Financial system stress (low probability, high salience)

Under your assumptions, this is unlikely, but worth flagging.

What would have to go wrong

Interest rates rise sharply while prices fall

Or unemployment spikes

Or construction collapse feeds back into credit losses

Absent those:

Canadian mortgages remain mostly full-recourse

Loan-to-value ratios stay manageable

Banks absorb it

This is not a 2008-style setup.

Why Aren't Federal Affordable Housing Initiatives Designed to Build Affordable Housing?

I recently came across a fascinating piece analyzing why publicly-funded affordable housing projects cost so much more in Chicago than in Houston. Much of the problem came down to the criteria used by the Illinois Housing Development Authority (IHDA) to allocate tax credits:

Solving the Housing Affordability Crisis With This One Cool Trick

The Audit has a growing library of posts addressing the housing crisis. I’m particularly proud of my Solving Canada’s Housing Crisis because of how it presents a broad range of practical approaches that have been proposed and attempted across many countries and economies. But the truth is that the

The Housing Crisis: One More Kick at the Can

The federal government has no shortage of initiatives designed to solve our housing sorrows. For the record, those programs include:

I think the most overlooked part of your simulation is the municipal panic. I was looking at the public accounts for Toronto recently, and it is wild how much their budget relies on land transfer taxes and development charges (basically the cover charge developers pay to build). If housing prices actually dropped 16% like your model suggests, big city mayors would be banging on the door of the Finance Department in Ottawa demanding a bailout within months. It creates a perverse incentive where the government literally cannot afford to let housing become affordable.

I really appreciated reading this thoughtful post.

I think an additional policy tool is to better regulate foreign ownership, and have additional taxes on homes owned by foreigners. State of Hawaii does this to out of state owners for example, and provinces could do same. So an Alberta buying a holiday property in BC, or an Ontario person buying in PEI, would pay additional out of province tax fees on their property each year. Need a mechanism to reduce demand of non local ownership without actually banning it.