How Does Canada Measure Poverty?

If a society hopes to manage welfare safety nets and economic policy intelligently then it’ll need clarity on who’s poor. Governments will often define poverty using some kind of poverty threshold representing the minimum costs of providing the basic needs for a given household type in a given location. Families earning less than that amount are considered “poor” and, therefore, entitled to financial support.

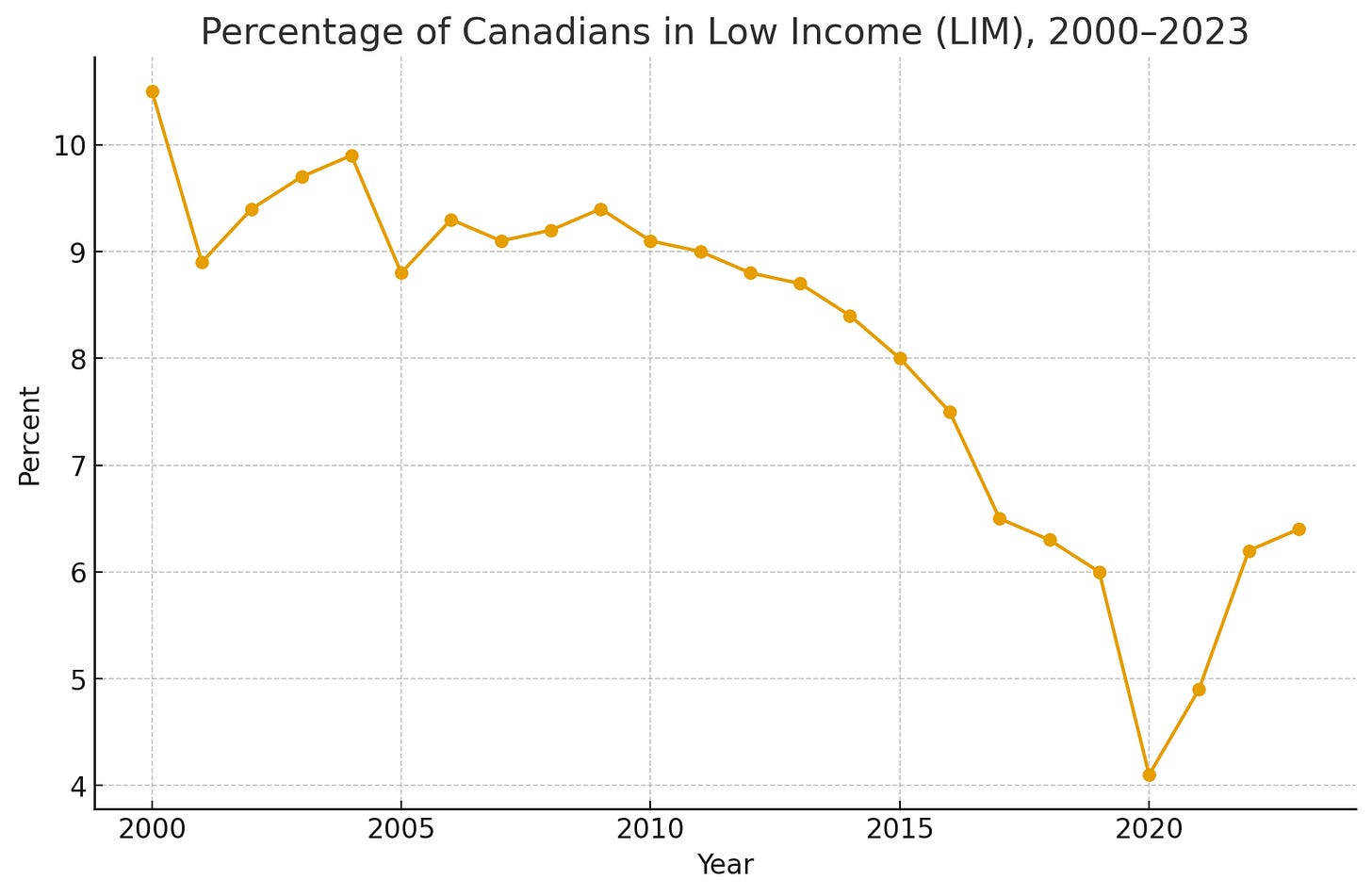

In fact, until just a few years ago, things had been steadily improving on the poverty front. This chart represents the percentage of persons in low income households using Statistics Canada’s Low Income Measure. If you ignore the COVID weirdness, you can see things are now heading in the wrong direction:

For this post, however, I’m more interested in the actual mechanics of measuring poverty. Just how well do the measures we’re using reflect reality?

Statistics Canada’s Market Basket Measure (MBM) assesses how much money is required to purchase the basic necessities for a simple, modest household. Cost estimates for up to 66 geographic regions have been published annually since 2002.

The 2024 MBM for a two-parent, two-child family in Toronto is $60,478. Life in Moncton, New Brunswick will cost you $54,116. And a family in rural Alberta can expect get by on just $51,217. By far the largest component of Toronto’s MBM is shelter expenses, which come to $26,290 (around 43 percent of the total MBM).

Let’s test that official shelter costs number for Toronto.

According to the City of Toronto, the most recent average market rent rate for a three bedroom apartment is $2,268 - which would come to $27,216 over twelve months. And that doesn’t cover utilities. Typically, most Toronto tenants will pay for their electricity over and above their base rent, and many will also pay separately for water and heating. So the real shelter costs for our “reference family” are likely much closer to $30,000 than $26,290.

But we’re not yet quite ready to fully understand those numbers. You see, the City of Toronto takes their average market rent rates from CMHC Rental Market Survey Data Tables. One problem with those numbers is that they measure structural rental affordability. In other words, they’re only looking at the rental rates for occupied units.

But don’t forget that most long-term tenants pay legacy rents suppressed by rent increase protections. It’s unlikely that newcomers looking for units would get anything like those prices. And because around 58 percent of Canadian tenants remain in their apartments for less than five years, in any given year thousands more people will be hit with rental rates far above the CMHC numbers.

We can see this is true from actual market data. Rentals.ca, for example, reports that the price of the current average listing for a two bedroom apartment in Toronto is $2,890.1 Those CMHC number’s certainly aren’t wrong. They do, after all, represent at least some of the costs faced by many tenants. But they’re also far from the whole story.

On the other hand, the MBM numbers are going to be a lot more difficult to explain. The official total shelter costs of $26,290 are a long way from the $36,000 or so that moving into a two bedroom apartment will cost in the real world.

Here’s another consideration. According to CMHC, the vacancy rate for two bedroom apartments in Toronto is just two percent. And vacancies for three bedroom apartments are a microscopic 1.4 percent. That means it’s unreasonable to expect a young family searching for a place to live in a red-hot competitive rental market to find housing for below-average rates.

Now, if the actual annual shelter costs for a modest rental in Toronto are around $10,000 higher than the official rate, in what way is the MBM an accurate representation of the true cost of living?

Here’s more related reading:

Solving Canada's Housing Crisis

Our housing crisis has been growing for decades, but recent years have driven things to a whole new level of dysfunction.

So What ARE We Supposed To Do With the Homeless?

Sometimes a quick look is all it takes to convince me that a particular government initiative has gone off the rails. The federal government’s recent decision to shut down their electric vehicle subsidy program does feel like a vindication of my previous claim

Do High-Rise Developments Depress Fertility Rates?

Canada’s sharp downward trend in fertility rates has appeared in this space before. For many reasons I see this as a looming crisis. Here, to refresh your memory, is how Canadian fertility rates per female have looked since 1991:The Audit is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscr…

It’s interesting that Rentals.ca tells us that those numbers are actually around seven percent lower than a year ago (when that CMHC survey was run).

Given that housing costs are a significant item in today's topic, I offer a radical free market perspective from Walter Block. Be sure to read "all" the comments. https://financialpost.com/opinion/opinion-cheers-for-slumlords