Do High-Rise Developments Depress Fertility Rates?

Canada’s sharp downward trend in fertility rates has appeared in this space before. For many reasons I see this as a looming crisis. Here, to refresh your memory, is how Canadian fertility rates per female have looked since 1991:

From a policy perspective, we should be thinking about creating economic and social conditions that encourage larger families. The problem is that the tools we’ve been using for many decades - like child tax credits, paid family leave, and subsidized childcare - simply haven’t worked to solve this particular problem.

So we could either throw up our hands in failure or look for something new. One area that would seem to be both relevant and within the scope of government responsibility is housing density. For example, is it wise for any level of government to push high-density, high-rise development at the expense of single-detached homes?

Intuitively I’d say that this is a no-brainer. Given a choice, which family wants to raise three or four kids in a 12th floor condo or rental? How many condos and rental properties of that size even allow occupancy with three or four kids? With that in mind, we would expect residential areas with more taller buildings to be less attractive to larger families.

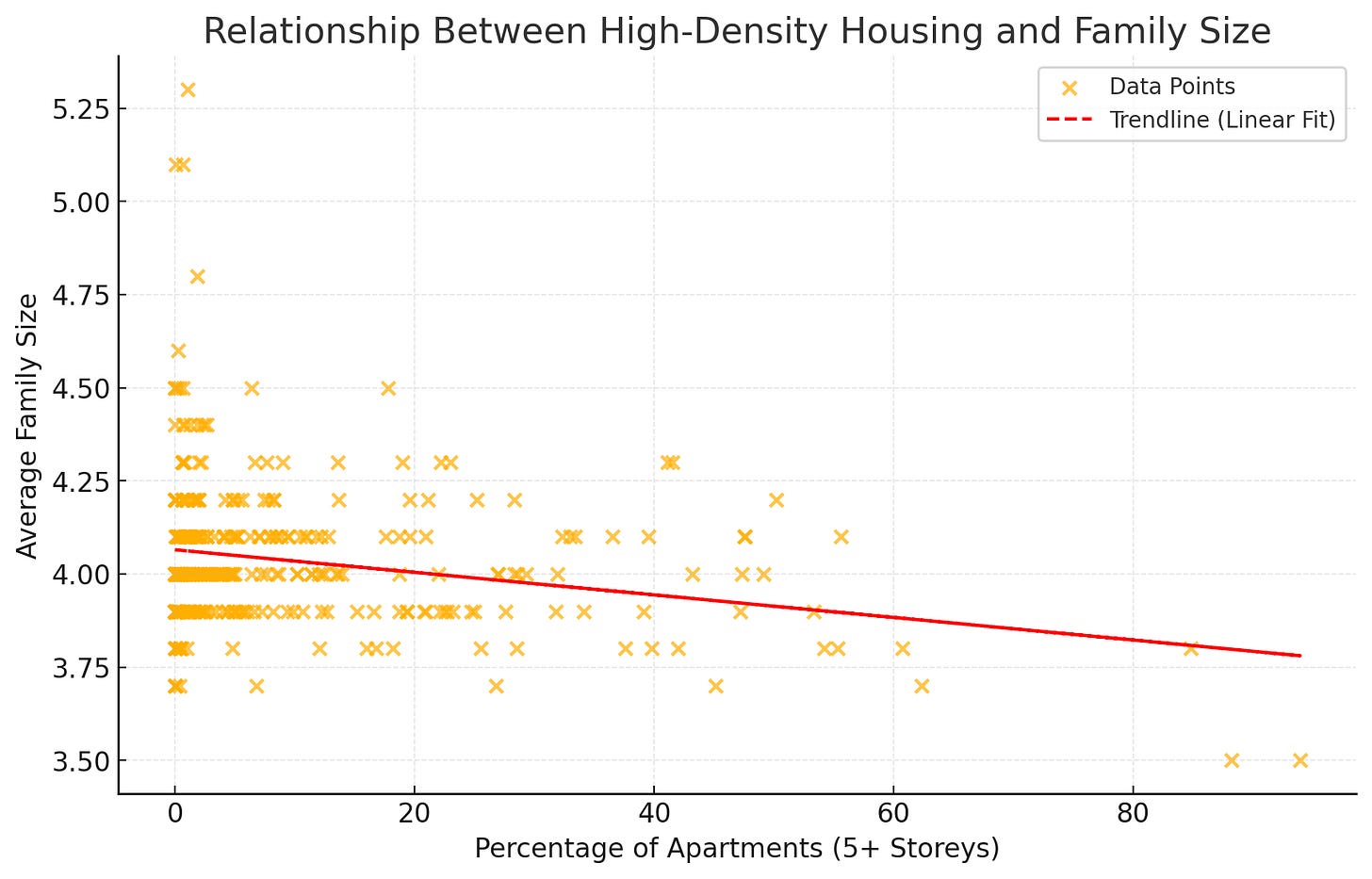

2021 Census data available from Statistics Canada should be able to help us here. I identified the percentage of apartments in buildings that have five or more storeys and the average family size of couple-with-children economic families for each of Canada’s electoral districts. I’d expect ridings with a greater percentage of high-rise apartments to have a smaller average family size.

I was wrong.

The correlation coefficient between the percentage of apartments in buildings with five or more storeys and the average family size is approximately -0.224. This indicates a weak negative correlation, suggesting that as the proportion of high-density housing increases, the average family size slightly decreases. But the relationship is not strong enough to suggest a clear, reliable pattern. This scatter plot shows us the results:

Well perhaps denser developments aren’t discouraging larger families, but could they be preventing couples from having any kids at all? To test that possibility, I pulled the riding-by-riding data for Total number of census families in private households with children and compared that to building density.

Nope.

The correlation coefficient between the percentage of apartments in buildings with five or more floors and the percentage of census families with children is approximately 0.157. This indicates a very weak positive correlation, suggesting a slight tendency for areas with higher-density housing to have a slightly higher proportion of families with children. But, again, the relationship isn’t nearly strong enough to draw useful conclusions.

Disproving an intuitive assumption might be disappointing, but it does represent an important step forward: at least we now know where not to invest our funds and energy. Other possibilities worth exploring could include ways to restore the social centrality of marriage (a known indicator of higher fertility among its many other benefits) and removing the excesses in educational messaging lingering from Paul Ehrlich’s widely-debunked overpopulation scare.

As Greg, Ross and Steve indicate, we have here a severe case of "missing variables." Simple correlation coefficients can be very misleading then. In a more complete model your intuition may very well turn out to be true.

The sharp changes in fertility rates over 1991-2023, up and down, would seem to be the first matter to be explained.

Great post. In Vancouver, where housing is super-expensive, Jens von Bergmann has drilled down to census-tract data. It turns out that the number of children (aged 0-15) is falling in low-density neighbourhoods, and rising in high-density neighbourhoods. In Vancouver, families can afford to live in multifamily housing, not expensive single-detached houses. https://morehousing.ca/children