Do Government Research Grants Support Research?

If you’ve been hanging around The Audit for long enough you’ll have seen my assessments of the limited value of some publicly funded academic research. But this post will ignore the quality of the research and focus instead on how much money is spent through the process of competing for grants themselves.

The largest source for research funding in Canada is a set of agencies now operating under the Tri-agency grants management solution (TGMS). The three participating agencies are Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

I’m curious to know how much it can cost institutions just to apply for grants. There may be no application fees to pay, but that would hardly be the only expense involved. And at a certain point, application costs can rise so high that the value of the grants themselves is effectively null.

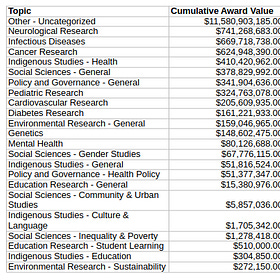

For this post, I’m going to work with data representing CIHR grant awards for 2024. There were 2,875 individual awards from that year worth an average of $248,264.

It’s interesting that average award amounts over the past few years have fallen significantly since a decade previous. The 2015 average, for instance, was $779,083 which is more than three times the 2023 or 2024 average. Throughout all of that time, total grant amounts have added up to more or less a billion dollars a year. So it seems that a stable pool of funds is being shared among more recipients.

That $248,264 average from 2024 is skewed by a few extremely large awards at the very top. When you look a bit deeper into the numbers, you’ll find that one quarter of all grant winners took home less than $33,000 each, 75 percent got less than $150,000, and fully half of them received less than $100,000.

Not every application is successful. In fact, only around 16 percent are accepted. That means that research institutions will face at least some expenses six times for every successful outcome, further increasing the overall institutional overhead.

What can grant applications cost in Canada? Here’s a break down of the costs that a typical application might face:

Faculty time: $7,500. Full or part time employees will use paid hours to prepare application documentation.

Research office and pre-award administration: $1,000. Labour devoted to performing eligibility checks, budget review, approvals, submission, and compliance.

Financial/contracting review: $1,000.

Internal review, editing, and support: $1,500. Time and materials involved with proposal editing; data management plan support; internal peer review; and mandated equity, diversity, Inclusion compliance statements.

Ethics review board charges: $4,500.

Systems and overhead attributable to applications: $500. Grant management systems, compliance tracking, and IT support.

That would come to a total of $16,000. Now when you factor in the likelihood that five of every six applications will be rejected, a single success will come with a cumulative cost of $96,000. Which is just $4,000 less than the median award amount we referenced earlier.

Which begs the question: if there’s virtually no net benefit for most grant applications, why do they bother with grants in the first place?

Now, it’s true that some of those costs might have been necessary even if the research was funded internally. Ethics reviews and peer review are good examples. But I’m guessing those elements make up a tiny fraction of the total costs.

I should note that some indirect institutional costs are recovered through the federal government’s Research Support Fund (RSF). But those payments are designed to cover ongoing research-related expenses that will often have nothing to do with grant application processes and could just as easily be directed to support internally funded research.

Keep reading:

Health Canada's Study on Heat-Related Deaths Is Good, but Misses the Point

Health Canada recently released a study on heat-related morbidity and mortality in Canada. The goal was to identify increasing harm and deaths caused by warmer weather events leading to heat stroke and heat exhaustion.

The Health Research Funding Scandal Parading in Plain View

Right off the top I should acknowledge that a lot of the research funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) is creative, rigorous, and valuable. No matter which academic category I looked at during my explorations, at least a few study titles sparked a strong “well it’s about time” reaction.

Veterans Affairs: Research Funding

I recently published an attempt to understand how the federal government cares for our veterans. If you haven’t yet, do take a few minutes to read about how hundreds of millions of dollars travel through dizzying layers of agencies and middlemen before they’re (presumably) spent on vets.

Long ago, the Federal government's main vehicle for public research was government labs (NRC etc.). This approach means little overhead to allocate research funding, but the Feds paid all of the costs, and over time became disappointed with what the labs produced. The Feds moved on to universities.

For more than 45 years, the federal government funding to universities has taken advantage of the provincial funding these institutions already receive for education and research. The Feds' funding is credited with research that produces lots of research knowledge and trained personnel (students) ... across the country.

The application success rate problem is a consequence of this approach: there are multiple independent stakeholders - the Feds, the provinces, the universities, and their quite-independent university faculty. The application churn noted in the post results in a dynamic competition of ideas, and the application load is only a minor inconvenience to the federal funding agencies (their grant evaluation costs are minor compared to the application preparation costs). Meanwhile, the organizations who pay for most of the application preparation costs (the provinces and universities) have so far been unwilling to restrict which professors are allowed to apply for funding.

On a side note, the post has an interesting estimate of costs to apply for CIHR funding - I was wondering where the estimated costs came from. For another view on the costs of applying for research, this paper has estimates of costs to apply for Australian Medical research funding: "The modified lottery: Formalizing the intrinsic randomness of research funding" by Steven De Peuter and Stijn Conix .

The calculation that it costs $96,000 to secure a $100,000 grant is startling. It highlights a hidden "tax" on research. We track similar complaints in the Hansard records from the House of Commons science committee. Witnesses frequently tell MPs that applying for funding has become a full-time job. However, the government’s Main Estimates (the annual spending plan) never account for this lost time. We are effectively paying our smartest people to fill out paperwork instead of doing science.