From Decline to Durability: Is the Traditional Family Bouncing Back?

I’ve written in the past about the economic and social benefits of strong families. But it may be worth taking a quick look at the current status of marriage as an institution in Canada.

Between 2000 and 2023, Canada’s population grew by around 31 percent. Over that time, the raw number of what Statistics Canada calls “couple families” grew even faster: from 7.1 million to 9.5 million - an increase of 34 percent. Through those same years, one-parent families grew in number by just 18 percent, significantly reducing their share of the total population.

But the increases in couple families haven’t been uniform. Couples whose older adult was between 25 and 34 years old in 2023 were 28 percent more numerous than in 2000, while there were only one percent more of those whose older adult was between 45 and 54 in 2023 than in 2000. By contrast, there were 54 percent more “55-64 year old” families in 2023 than in 2000.

However, properly understanding those numbers will require some context. While there were 54 percent more 55-64 year old couples in 2023 than in 2000, there were also 86 percent more 55-64 year olds in the population as a whole. So the proportion of couples in that age cohort has actually dropped over time.

In fact, as the chart below illustrates, no age cohort saw an increase in their proportional rate of marriage (or at least common-law relationship) participation:

On the other hand, the durability of the marriages Canadians do undertake is definitely recovering from a long-term decline. For some reason, Statistics Canada has no divorce-related data more recent than 2020. But what we do have clearly shows the duration of the average marriage climbing to as high as 15.6 years after decades in the 12 to 13 year range.

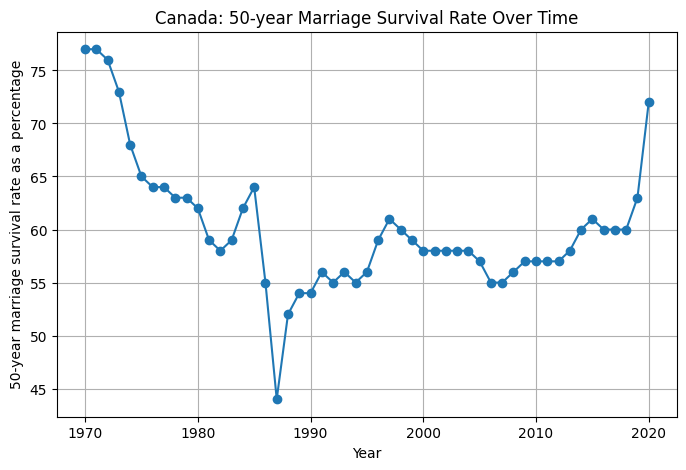

And the 50-year total divorce rate1 has been visibly dropping. Put differently, the percentage of couples whose marriages did not end in divorce before their fiftieth anniversary (i.e., the inverse of the 50-year total divorce rate) has been trending upwards for the best part of a decade now:

The Divorce Act of 1968 and subsequent amendments to the Act in 1986 made it easier to receive a relatively painless and quick divorce. While that doesn’t explain why more people sought them in the first place, those legal changes certainly triggered a sharp increase in divorces.

Given everything we now know, was introducing no-fault divorce rather than focusing on strengthening complainants’ access to at-fault claims the right policy choice? These days, we’re so used to the no-fault system that it’s difficult to even imagine a counterfactual.

Besides changes to divorce law, the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) - through Section 15 - enshrined equality rights, thereby empowering women economically and reducing dependency in marriages. This probably also contributed to higher divorce rates and lower marriage participation.

Expansions in parental leave and child benefits through the Canada Child Tax Benefit introduced in 1993 supported family formation and stability and could explain at least some of the subsequent reversal. And recognition of common-law unions in federal benefits and tax policies might have helped reduce divorce rates by diverting less committed couples from marriage altogether.

More recently, the housing affordability crisis seems to be forcing younger Canadians to delay their marriage plans. This could have led to more stable relationships (while at the same time contributing to suppressed birth rates).

Marriage is an institution that’s central to the success of families. And any government serious about building strong and nurturing communities will deploy all the policy options it has to encourage the creation of stable families. We’ve now got a half century of relevant experience from which to draw.

“The 50-year total divorce rate (TDR-50) is the sum of duration-specific divorce rates up to 50 years of marriage. It can be interpreted as the proportion of married couples who would divorce before their 50th wedding anniversary if the duration-specific divorce rates observed for a given year remained constant. This rate does not take into account mortality and migration.”

Forty-eight years, this year. Our secret? We’ve always agreed that if we win big in the lottery I’ll buy my wife a house in the country - and myself a house in another country! :-)