What Does the Federal Government Really Look Like?

A big-picture view of some public service hiring and spending trends

This post originally appeared in the book: Adventures in Canadian Policy: data stories from the land that competence forgot.

Change is normal. The world around us isn’t sitting still and that’s got to have an impact on what’s needed by Canada and Canadians. So we can expect a government’s size and shape to evolve over time, but we’d certainly prefer that the changes were rational.

So let’s take a few minutes to understand how the size, cost, shape, and mandates of our government have been changing over the past few years.

Public service employment

Governments provide a set of services that don’t change dramatically from year to year. Sure, as the population grows they’ll need to process more passport applications and oversee the movement of greater numbers of international travelers across our borders. But task complexity shouldn’t increase faster than the population itself.

Therefore you would expect that the public service should grow in proportion to the overall population. Well, that’s not really true. Due mostly to digital automation, Canada’s private sector labor productivity rose steadily between around 1990 and 2014 and has maintained its peak level ever since. So in fact, since we can now do more with fewer people, you’d really expect public sector employment not to keep pace with rising population levels.

However, the actual proportion of federal employees to Canada’s total population has been growing noticeably over the past six years. Because of the scale I chose for its y-axis, the graph below does exaggerate the changes a bit, but you can see how the federal workforce grew from around 0.72% of the total population in 2017 to 0.9% in 2023. That means about one out of every 59 employed Canadians now works for the federal government.

Which means that – worker-for-worker – Canada’s public service is significantly less productive than it was ten years ago. And the growth in absolute numbers from 257,034 workers in 2015 to 357,247 in 2023 can be accurately characterized as bloat. Unforgivable bloat.

Departmental employment

Since 2011, by my count (and based on Treasury Board data), 11 new federal departments or agencies have come into existence and 18 have been shuffled off to wherever it is old bureaucracies go when they die. In some cases, the change represents nothing more than a technical realignment. The move from the Canadian Polar Commission to Polar Knowledge Canada is probably one such example.

I’m mildly curious to know how much such changes cost, even in terms of simple details like outsourcing designs for a new letterhead and getting IT to set up (and secure) a new website and email domain. I’m sure those don’t come for free.

It’s noteworthy that 11 of those 18 shutdowns took place in 2015 and 2016. That suggests they were the result of the incoming Liberal government’s policy implementations. Nevertheless, those changes don’t explain the scope of civil service employment growth since 2015.

The next graph fills that void by showing us the departments which experienced the largest employment increases and decreases between 2010 and 2023. None of the departments that were either created or discarded over those years – which, for the most part, were smaller organizations anyway – were included.

Let’s explore those changes.

The significant drop suffered by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada occurred around 2020 and was the result of the creation of the new Indigenous Services Canada department. Net employment actually grew by around 4,000 workers.

The reduction for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada happened mostly between 2012 and 2014 and appears to have been part of general cost-cutting measures during the Harper years. There were similar reductions in Health Canada during those years, but they’ve since recovered around two thirds of their lost workforce.

The big story from that graph is the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). They went from a workforce of just 39,494 in 2016 to 47,426 in 2021. But the largest jump came after 2021. By 2023, there were nearly 60,000 people at the agency competing for the most comfortable office chairs and programmable coffee makers.

Some of the growth can be attributed to the expanded responsibilities associated with administering and enforcing compliance for COVID-era benefits including the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Efforts to modernize around 2016 likely also contributed to hiring increases.

But CRA’s own documentation informs us that a major driver of hiring increases has been the agency’s employment equity efforts. In fact, they wrote that “the change in internal representation over a one-year period” was 4,198. That number is a near-match to the actual employment increase between 2022 and 2023 based on our Treasury Board data. This suggests that all new hires have been of “equity-deserving group members” as opposed to “non-equity deserving groups” (in CRA’s bizarre terminology).

COVID programs might also explain how Employment and Social Development Canada added more than 11,000 members to their rolls since 2020. Why those numbers didn’t drop again in 2023, which was long after the emergency had ended, isn’t clear.

The jump in employment at Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada – which more than doubled from just 4,850 in 2013 to 12,258 in 2023 – can easily be blamed on the well-documented immigration surge that’s become the hallmark of the Trudeau years.

The bottom line is that policy decisions require resources, infrastructure, and human beings to execute. And all of those cost money.

Departmental spending

I’m sure no one will fall into a shock-induced faint when I tell you that federal spending has increased over the past ten years. There were 36 departments that spent more than one billion dollars each in fiscal 2022-23, as opposed to just 26 in 2013. Here are the sobering totals based on Government of Canada InfoBase data for both the 2013-2017 and 2018-2023 periods:

Breaking those numbers down by individual departments will give us some more important insights into what’s been driving budget bloat. Here are the 20 departments that experienced the greatest spending growth over the past ten years:

Expenditures by Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) rose from $49.6 billion in 2013 to $88.1 billion ten years later. Spending peaked in 2021 at $162.6 billion, but that was obviously due to COVID (the gift that keeps on giving). But even ignoring 2021 and 2022, the ten-year jump was still 77 percent.

Diving a bit deeper, we see that spending for some ESDC programs grew faster than others. Here are programs that, since 2018-19, increased the most:

Remember: that’s just program growth. The actual 2022-23 combined spending for Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (which are both elements of the Old Age Security Act) was $68.8 billion. That’s more than 17 percent of the total federal budget. As the last of the boomers reaches retirement age, that percentage will only grow.

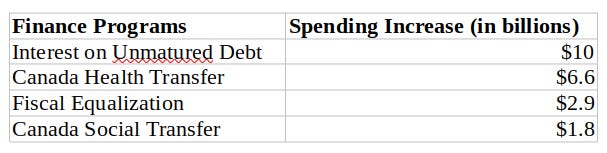

Department of Finance Canada’s overall budget – which grew from $85 billion in 2013 to the most recent year’s $117 billion – is focused mostly on provincial and territorial transfer payments. Here are the programs generating the highest increases:

The significance of that $10 billion in payments for unmatured debt is that those payments don’t pay down any of the debt itself: it’s only servicing interest on existing debts. And that’s just ESDC. The total government-wide expenses on such debt in 2023-4 was more than $37 billion.

I am a retired accountant and I recall being advised many years ago that "numbers never lie but liars always figure" and I can see that aphorism expressed in your analysis.

Clearly, clearly, we are seeing vastly increased money being expended - oh, sorry, I mean "invested" [absolutely NOT an investment!] - and head count immensely increased. At the same time, the quality of services as measured in time to accomplish something (anyone for a passport?) or for someone to even bother to try to accomplish anything (care to try to chase down the billions sent out erroneously during COVID?) is "problematic" - being excruciatingly and stupidly polite.

My point is that your figures prove again that no matter the excuses from governments, particularly our current federal overlords, the liars continue to "figure."

I was interested to see the growth in numbers of employees at CRA and ESDC. Add to that, on the tax side, all those in the private sector who labour as tax lawyers and accountants. Are there any researchers modelling a radically different, less Byzantine and ornate, taxation model? One that would less costly to administer?

As to ESDC, would a basic annual income or some combination of other policies ease the process of redistributing resources.

I am happy to pay taxes. I think we are privileged to be taxed and to have tax dollars directed to defence and diplomacy, roads and rails, education, health and income support.