The Hollow Emptiness of Canadian Electoral Representation

A couple of months back I wrote about how real-world political representation for Canadians can be deeply unequal. One vote does not have the same power in PEI as it does in BC. And, in any case, the individual MPs we elect are largely powerless to do anything meaningful on behalf of their constituents.

To be sure, the recent federal election was reasonably fair and clean. But as a recent Globe and Mail piece by Andrew Coyne claimed, so much uncontested political power in Canada lies in the hands of the tiny staff in the prime ministers’s office that it’s hard to see how what connection voters have to the seat of real power in the country.

Those are provocative words. So I thought I’d see if I could measure the problem. Just how broken is democracy in Canada?

We’ll begin with your vote. We might all have get the same ballot at on election day, but where the ballot box happens to be will make a huge difference to how well you’re represented. According to Elections Canada, an MP elected in the Labrador electoral district only needs to represent 26,655 constituents, while the MP from Edmonton--Wetaskiwin (at least until the redistribution which took effect this year) had 209,431 opinions to worry about. Overall, the average population size of all ridings throughout the country was 109,444.

If you average out all the ridings within each province, 143,786 Albertans have to compete for the attention of each of their MPs, something necessary for only 44,638 citizens in PEI.

For complex historical reasons, representation numbers in the Senate are skewed even more dramatically. While nation-wide, the population-to-senator ratio is 286,967-to-one, that jumps to 949,738-to-one in BC, and drops to 41,738-to-one in Nunavut. In other words, it’s significantly easier for some Canadians to access their federal representatives than it is for others.

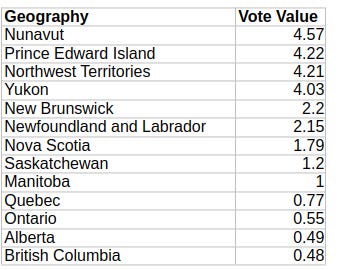

How significantly different does it get? I combined those Parliamentary and Senate ratios and calculated a “score” that describes the value of a single vote in each province or territory in relation to the overall average (here designated as “1”).

As you can see, the value of a vote in Manitoba is worth roughly the same as the national average. Each vote cast by people in the territories and maritime provinces is worth considerably more than elsewhere. In fact, Nunavut ballots carry more than ten times the influence of the same piece of paper in Alberta or BC.

Of course, the imbalance goes far deeper than the provincial level. Our first-past-the-post electoral system means that the 407,324 Toronto voters who backed Conservative candidates in the last election have just one sympathetic ear in Ottawa to approach for help. And the 27.9 percent of Albertans who futilely voted Liberal are similarly denied local representation.

All that’s no one’s fault. Even if our electoral system has its problems, I’m not sure there’s anything out there that’s necessarily better. The Americans spend countless billions of dollars each election cycle and I doubt anyone is particularly happy with the process. The Israeli system is certainly admirably representative - just listen to the intensity of debates in the Knesset or its committees - but it invariably results in hopelessly chaotic coalitions where meaningful legislative reform is virtually impossible.

But, as Coyne points out, the tight, top-down party discipline in Canadian politics means that candidates are often chosen by party leadership rather than riding associations, leadership campaigns are dominated by one-off membership drives rather than long-time party loyalists, and MPs and even cabinet ministers can rarely escape stifling party-line voting and party-approved messaging.

Besides effectively controlling Parliament, the Prime Minister - for all intents and purposes - decides who occupies nearly every critical unelected office in the country, including:

Cabinet Ministers

Senators

Lieutenant Governors (provincial)

Supreme Court of Canada Justices

Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal Judges

Tax Court of Canada Judges

Clerk of the Privy Council (head of the federal public service)

Deputy Ministers of federal departments

Heads of Crown corporations

Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS)

Commissioner of the RCMP

Governor of the Bank of Canada

Chief Electoral Officer

Parliamentary Budget Officer

Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner

Auditor General of Canada

Privacy Commissioner and Information Commissioner

Ambassadors and High Commissioners

Heads and Members of Regulatory Agencies

Immigration and Refugee Board members

Canadian Human Rights Commission

While, by accepted tradition, the decisions governing many of those choices were shared broadly and tempered by fairness and consent, there are no significant legal checks on a Prime Minister’s powers.

And it’s not like we even have a functioning Parliament in the country. For the nine months between last December and this coming September, Parliament will probably have spent no more than a few short weeks in session. Has anyone even noticed?

Right now, a Canadian Prime Minister and his small inner staff effectively play the role of a U.S. President, but without the checks of an often hostile Senate, Congress or Supreme Court.

Since we’re talking about numbers, there’s another claim I made on that earlier post that’s at least tangentially relevant to this discussion. I wrote:

Francophones have stronger representation in the federal public service due to official bilingualism policies, even in provinces where French is not widely spoken.

In fact, as of the 2021 census, 22 percent of all Canadians speak French as their “first official language” while fully 30.51 percent of the federal public service spoke French as their first official language. That probably means that influential positions in government are indeed being filled by francophones beyond their proportion in the general population.

That’s not to suggest that francophones aren’t executing their roles in the public service as faithfully and effectively as their anglophone colleagues. But the demographic reality is that the influence of non French speakers over society is, proportionally, likely being subtly and incrementally diluted.

Happily, I earned my promotion within the federal government partly because my position was deemed ‘bilingual’ and I met that criterion. It’s the way that The System works but I can’t say that I agree with it. I encountered many a civil servant who was *officially* bilingual but who really couldn’t conduct a meaningful conversation in their second language; they’d just passed the government language school programme, which generally teaches bureaucratese. A year or two later, having hardly needed their French on the Prairies, they’d lost their vocabulary but remained in their position as their language profile was valid for five years.

Excellent! I love your figures.