How Representative Is Your Government?

What can parliamentary voting patterns tell us about the primary loyalties of our members of parliament?

Is Canada’s parliamentary system of government democratic?

Yes. Next question?

Ok. But how representative is it? Well that’s something worth exploring. First, what do I mean by “representative?” It’s not necessarily intuitive that all governments need to consider the will of their citizens when setting policy. I don’t believe China’s National People’s Congress has any legal obligation to consult with its people or even consider their thoughts. Technically, our government rules in right of sovereign of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth realms who could, in theory, tell us how they’d like things run.

Through decisions made centuries ago by ancestors and predecessors of King Charles III, our system is founded on popular elections. That means our legislators are chosen by us and, for all intents and purposes, govern in our right. So every few years we get to throw the old set of representatives out and choose the next herd.

But what about in between elections: where do our members of parliament look for their day-to-day instructions? I believe some simple data analytics can help us answer that question. I’m going to see how often members of parliament vote strictly along party lines. If they’re always following their party leaders, then it would seem it’s the parties who they serve. If, on the other hand, they often cast votes independently of their parties, then they might be thinking more about their own constituents.

This won’t definitively prove anything one way or the other but, if we can access a large enough data set, we should be able to draw some interesting insights.

Parliament’s Open Data project is an excellent resource to get us going. We’ll begin with the Votes page. The main data on this page consists of a table listing all the bills associated with a particular parliamentary session.

A parliament, in this context, is all the sittings occurring between the formation of a new government after one election, until its dissolution before the next election. A session is a few months’ (or even years’) worth of sittings. The second session of the 41st Parliament (which stretched from October 16 2013 until August 2, 2015) would be represented by this URL:

https://www.ourcommons.ca/Members/en/votes?parlSession=41-2

That URL would present you with links to all the votes from that session. If you preferred to see only private members’ bills from that session, you could add the bill document argument: TypeId=4. Substituting TypeId=3 for that, as with the next example, would return all house government bills. This example points to house government bills from the current session (the second session of the 43rd parliament):

https://www.ourcommons.ca/Members/en/votes?parlSession=43-2&billDocumentTypeId=3

If you’d prefer, you can move between views on the website itself through the various drop-down menus. But to get the sheer volume of data we’re after, we’ll need the power of some well-written Python code.

What’s the difference between members and government bills? The former are sponsored by regular members of parliament of any party, while the latter are always sponsored by cabinet ministers and reflect the government’s official position.

I would expect that parties are more likely to at least try to force the compliance of all their members when it comes to voting on government bills. Private members’ bills would, perhaps, be more likely to encounter independent support or opposition. It also seems likely that we’ll find more fractured voting among opposition parties for government bills than for members of the government. Dissension should, by that same token, be equally present within all parties for private members’ bills.

Let’s see if the data bears out our assumptions. I scraped voting records for all 439 votes in that second session of the 41st parliament. I filtered out unanimous votes, since they’re often focused on non-controversial topics like honouring individuals or institutions and will teach us nothing about normal voting patterns. On the contrary, the could skew our results.

What did we learn?

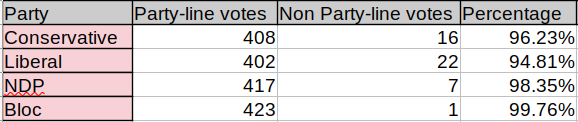

So here’s what came back from scraping all government-sponsored bills from session 42-1:

We counted 424 votes in total.

Conservative members voted the party line 408 times, and split their vote 16 times.

Liberal members voted the party line 402 times, and split their vote 22 times.

NDP members voted the party line 417 times, and split their vote 7 times.

Bloc members voted the party line 423 times, and split their vote 1 times.

Out of 424 non-unanimous votes (there were 439 votes in total), Conservative members dissented from their party line 16 times, NDP members seven times, and the Bloc only once. But here’s the interesting bit: Liberals - who, as I’m sure you know, were the government for this session - dissented more than any other group: 22 times. That’s more than 5%. So much for my assumption about governing parties and party discipline. (Or perhaps that’s a product of the relative quality of their legislative program.)

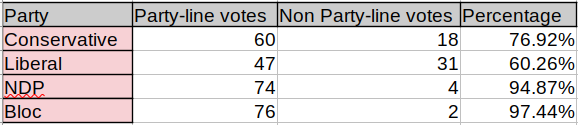

The results did, however, confirm a separate assumption: split votes are, indeed, more common for private members’ bills. Here’s how those numbers looked:

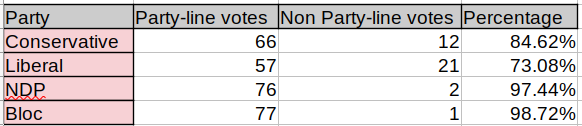

I did wonder whether my 0-vote threshold for split votes was too strict. Perhaps having just one or two rogue members in a party vote isn’t an indication of widespread independence. Would it be more accurate to set the cut off at a higher number, say 3? Testing this was easy:

That’s noticeably different, suggesting that there isn’t significant voting dissension among the ranks of our political parties.

Could government be more representative?

When everything’s said and done, our data showed that members for the most part voted with their parties at least 95% of the time. Given how they seem to vote, do we really need all those hundreds of MPs? Wouldn’t it be enough to simply vote for a party and let whichever party wins select cabinet ministers from among all Canadian citizens?

Of course, MPs do much more than just vote. They work on parliamentary committees and attend to the needs of their constituents through local constituency offices.

But why couldn’t parties appoint their own people to staff those committees? And why couldn’t qualified individuals without official links to a political party be hired to staff constituency offices?

Ok. Now how about the fact that, behind the scenes, party caucuses provide important background and tone that helps party leaders formulate coherent and responsive policies?

Yeah. Sure they do.

I’m not saying that MPs aren’t, by and large, hard-working and serious public servants. And I don’t think they’re particularly overpaid. But I’m not sure how much grass roots-level representation they actually provide.