Is Government Policy Making You Poorer?

And who can we blame?

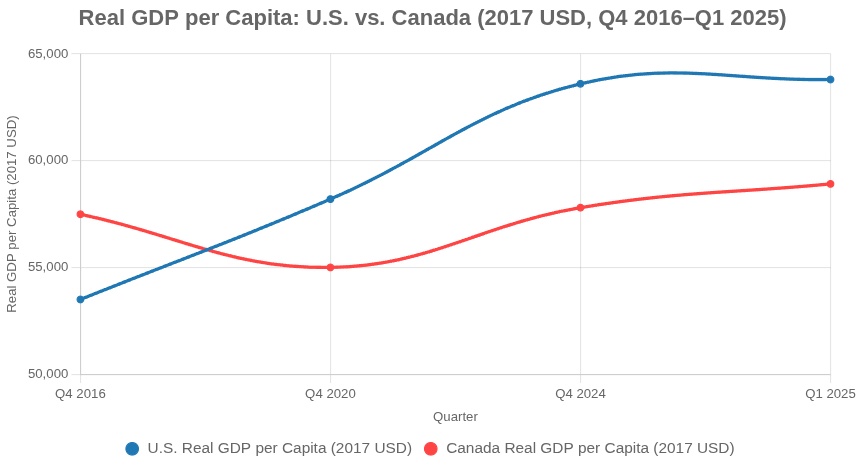

I’m sure that by this point, most of you have read about Canada’s dismal per capita gross domestic product (GDP) - especially in comparison with what’s happening in the U.S. Just to get all of us up to steam, the Canadian version of that key economic measure has been largely stagnant over the past decade, while things have been firing on all cylinders down south.

What’s driving our dismal performance? We can’t blame the whole thing on governments, but policy certainly plays an oversized role. The unsustainable rate of population growth, for example, has been entirely the product of federal government choices. This, in turn, has contributed to severe housing market constraints.

Labour productivity in Canada has been weak for years - far lower than in the U.S. - and is headed in the wrong direction. Overly complex regulations and slow permitting take some of the blame for poor investment numbers. Programs like the Canada Innovation Corporation and R&D tax credits exist, but haven’t made much of a difference. The OECD cites Canada’s low public and private R&D spending (1.7% of GDP vs. 2.7% in the U.S.) as a barrier. And government policies have also so far failed to address interprovincial trade barriers, reducing efficiency.

Weak technology adoption, regulatory hurdles, and sub-standard intellectual property protections - along with a hyper-politicized higher education culture - have, no doubt, both driven out smart Canadians and convinced talented foreigners that we’re not worth the risk.

So I don’t think I’m breaking any new ground by concluding that at least half of our GDP woes are results of public policy decisions.

But GDP isn’t the only measure of economic health. GDP, after all, is just a proxy for economic well-being. For some purposes, a better measure is purchasing power. That is, how much can we afford to buy with the money we actually have. For that, some version of the OECD purchasing power parities index can be useful.

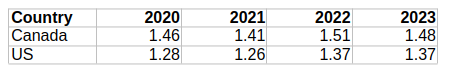

This first table compares the OECD’s household final consumption expenditure for Canada to U.S. numbers. By way of explanation, in 2024 - relative to OECD prices - it took 1.44 Canadian dollars to purchase what 1 USD could buy in terms of household consumption. The disparity hasn’t changed all that much over the five years for which we have data:

Another way of saying that is that Canadians pay about 20–30 percent more than Americans to maintain the same standard of living even after adjusting for prices.

The next table represents actual collective consumption, which is a measure of the true costs of government-provided goods and services, such as public education, public health, and police. Once again, a higher value means lower purchasing power of that country’s currency.

And once again, Canadians have to pay considerably more for otherwise equivalent services. Those numbers are unaffected by the public vs private healthcare differences: we’re only looking at the costs of those services that do come from governments.

Is it government policies that drive our purchasing power deficit? Well, it's certainly reasonable to say that zoning and land use laws restrict housing supply and lead to higher prices, as do higher consumption taxes (HST/GST). Similarly, interprovincial trade barriers inflate domestic distribution costs, foreign ownership restrictions for the telecom and airline industries reduce competitive pressure, and regulated costs for electricity, mobile phone, and internet services are significantly higher (due largely to limited competition and provincial monopolies). Add to that, Canada's protected industries (like dairy and poultry under supply management) which artificially inflate food prices.

So, yes. Government fingerprints can be found all over our weak purchasing power relative to our neighbours in the U.S.

The question is whether there any trade-off benefits we get as Canadians that compensate for our poor economic health. In other words, is this the governance that Canadians actually want?

End stage democracy has taken us from a prosperous free market capitalism to an arguably "sustainable government" and now to bankrupt leviathan in the last half century or so. Canada, starting in the mid 19th century started easing up on land grants retaining more Crown land (the start of the US lumber lobby irritant). Agriculture continued to develop with homesteading and railroad and some mining land grants before we "arrested development" as a relatively feudal nation of 89% Crown ownership (95% in BC). Never having ending the enshrined apartheid of the Indian Act (last attempt was the Chief-rejected "White Paper" of Trudeau/Chretien of 1969), we now have a massive grievance industry that ensures shakedown and grift on every major resource/infrastructure proposal and a Supreme Court that has advanced rulings which have raised grievance industry expectations along with submissive governments undermining their own sovereignty regarding title to Crown land. 54% of the private land under the city of Richmond BC has just been ruled as having aboriginal title by the BCSC. The Judge, not wanting to rule himself out of a job and a government, has ruled that there can be private land and Aboriginal title on the same land and its up to the Crown to resolve, I.E., borrow on the unborn taxpayers to pay off the Chiefs. This is the current mess of Canada and like all bankrupt leviathan states, a guaranteed outcome of end stage democracy-the irreversible point where the electorate realizes that they can vote for the contents of the treasury whether it's there or borrowed-on and from then on, the party that offers the most loot gets the most votes. Not mine, not Schultz's and others but the majority vote of the evolving Eloi (discovered by H. G. Wells' time traveler). Next step, due to bankruptcy is dictatorship (See Alexander Tytler 1747-1813)

"We can’t blame the whole thing on governments"?

Why not? Of course we can.