What's Your University Degree Really Worth?

Assessing a major university advocacy group's arguments in support of their product

Postsecondary education is big business. As a group, for instance, Canada’s hundred or so universities are said to be responsible for $40 billion in direct expenditures - and in Canada at least, a billion dollars will take you places.

So it would be nice if there was a way to clearly measure the value-per-dollar both customers (students) and funders (mostly taxpayers) can expect to earn.

Perhaps there is. Universities Canada (formerly the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada) is the primary advocacy group representing Canada’s universities. The Facts and Stats page featured prominently on their website exists to make the official case for Canadian universities through a number of focused bullet points.

Among other claims, the page asserts universities’ ability to deliver millions of high-paying jobs, create generational leaders, and drive economic growth.

Let’s explore those one at a time:

“Social science and humanities grads share in the income premium for university graduates. For example, full-time workers with degrees in history earn, on average, above $65,000 annually.”

That $65k income figure is a great place to begin. The site attributes this number to Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey. I couldn’t find that exact figure on the statcan website, although that certainly doesn’t mean it’s not there: there are many, many ways to slice and dice income data and navigating through them all isn’t for the faint of heart.

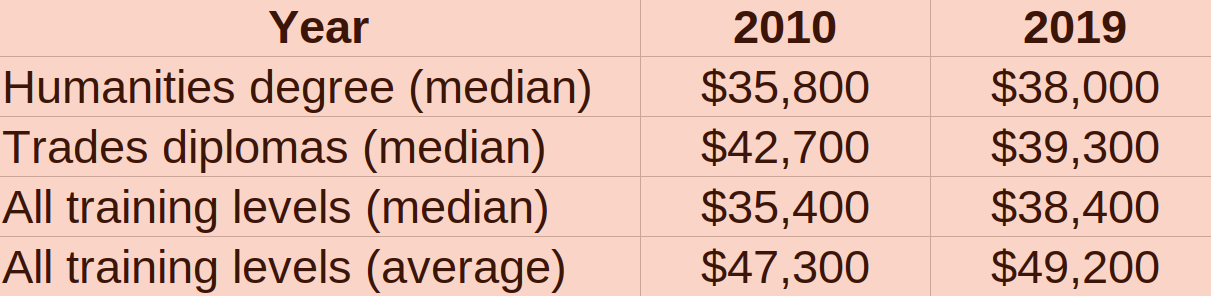

However I did find some closely related metrics. For instance, the median employment income of postsecondary humanities graduates two years after graduation was $35,800 in 2010 (using 2021 constant dollars), and $38,000 in 2019. For comparison, the median employment income across all fields was $35,400 in 2010 and $38,400 in 2019. The average employment income for all Canadians (including those with no postsecondary education) in those years was $47,300 and $49,200 respectively.

Here’s a more relevant comparison: the median employment income for individuals using diplomas to work in trades, services, natural resources and conservation actually dropped from $42,700 in 2010 to $39,300 in 2019. But that was still higher than those with humanities degrees, and the diplomas required much less time and money to acquire.

Here are all those numbers in an easy-to-view format:

So what might that $65k income number have represented? I can’t be sure of course, but I suspect the confusion has something to do with the many ways statisticians define “income”. There’s household income (all the money earned by members of your family), employment income (wages, tips, and salaries), market income (income from all sources, including investments and real estate), and after-tax income (which can include government transfers like tax credits and benefits).

But we do know the context of the employment income figures I’ve just quoted. And it would seem that, relative to the alternatives, a humanities degree most certainly does not guarantee a substantial livelihood.

55% of leaders are liberal arts grads. Source: British Council, Educational Pathways of Leaders: an international comparison, 2015.

Well, right off the bat, this one is going to be hard to validate. The British Council doesn’t really define “leadership” in an objective way and, in a footnote, also explained how:

“For the most part, only leaders with higher education qualifications were considered for this study in order to determine how higher education contributes to professional success.”

It seems that University Canada is trying to prove that a university education uniquely builds leaders using a study that focused exclusively on university graduates. Which kind of defeats the purpose.

But let’s give them the benefit of the doubt and assume the people they’re studying are all genuine leaders. I guess that means the 55% whose professional qualities were formed by their liberal arts educations are the ones primarily responsible for the precipitous decline in institutional trust, economic crises, and general political chaos throughout so much of the world. Hardly a stirring recommendation.

To properly make their point, Universities Canada would have had to demonstrate that their graduates were indeed leaders and that their leadership had been a force for good. They didn’t.

“Between March 2012 and March 2022, 2,169,700 new jobs were created for university graduates, three times as many as those created for graduates of all other types of postsecondary education combined.”

I won’t deny that a solid university education can open doors to important career advancement. In fact, I’m sure that many of the better job opportunities coming on line in fields like healthcare, engineering, and applied mathematics require degrees.

But industry trends suggest that things are changing. A recent Indeed study found that “67% of companies with 1,000 or more employees would consider doing away with the college requirement” with 26% of respondents reporting “that an applicant’s degree rarely matches the industry.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Audit to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.