Replay: What's Your University Degree Really Worth?

Assessing a major university advocacy group's arguments in support of their product

I’m currently involved with a couple of ongoing projects and with researching a promising but technically complicated new data source. Getting all that right is taking up a lot of the limited time I’ve got available. So for now, here’s an (updated) replay of a post from nearly a year ago when there was just a tiny handful of subscribers. Why waste perfectly good content?

Post secondary education is big business. As a group, for instance, Canada’s hundred or so universities are said to be responsible for $40 billion in direct expenditures - and in Canada at least, a billion dollars will take you places.

So it would be nice if there was a way to clearly measure the value-per-dollar both customers (students) and funders (mostly taxpayers) can expect to earn.

Perhaps there is. Universities Canada (formerly the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada) is the primary advocacy group representing Canada’s universities. At the time this post was originally published, this version of the Universities Canada Facts and Stats page was featured prominently on their website. The link leads to the Internet Archive version from that time. The page existed to make the official case for Canadian universities through a number of focused bullet points.

Among other claims, the page asserted universities’ ability to deliver millions of high-paying jobs, create generational leaders, and drive economic growth.

Bearing in mind that the first three of these four claims have since been removed from the University Canada site, let’s explore them one at a time:

“Social science and humanities grads share in the income premium for university graduates. For example, full-time workers with degrees in history earn, on average, above $65,000 annually.”

That $65k income figure is a great place to begin. The site attributes this number to Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey. I couldn’t find that exact figure on the statcan website, although that certainly doesn’t mean it’s not there: there are many, many ways to slice and dice income data and navigating through them all isn’t for the faint of heart.

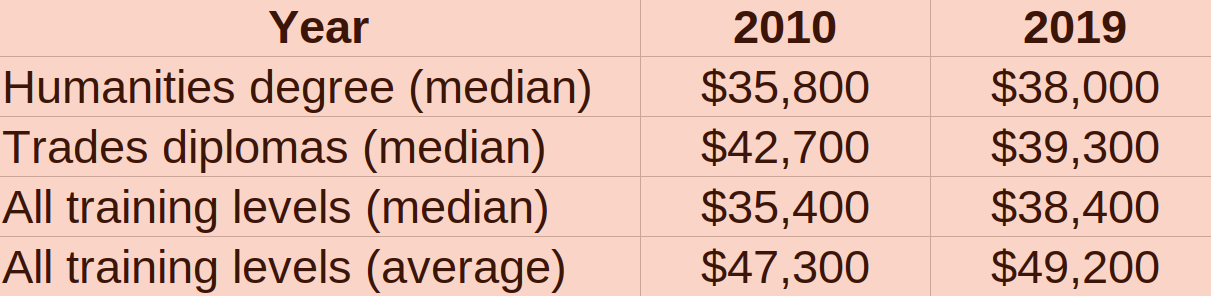

However I did find some closely related metrics. For instance, the median employment income of post secondary humanities graduates two years after graduation was $35,800 in 2010 (using 2021 constant dollars), and $38,000 in 2019. For comparison, the median employment income across all fields was $35,400 in 2010 and $38,400 in 2019. The average employment income for all Canadians (including those with no post secondary education) in those years was $47,300 and $49,200 respectively.

Here’s a more relevant comparison: the median employment income for individuals using diplomas to work in trades, services, natural resources and conservation actually dropped from $42,700 in 2010 to $39,300 in 2019. But that was still higher than those with humanities degrees, and the diplomas required much less time and money to acquire.

Here are all those numbers in an easy-to-view format:

So what might that $65k income number have represented? I can’t be sure of course, but I suspect the confusion has something to do with the many ways statisticians define “income”. There’s household income (all the money earned by members of your family), employment income (wages, tips, and salaries), market income (income from all sources, including investments and real estate), and after-tax income (which can include government transfers like tax credits and benefits).

But we do know the context of the employment income figures I’ve just quoted. And it would seem that, relative to the alternatives, a humanities degree most certainly does not guarantee a substantial livelihood.

55% of leaders are liberal arts grads. Source: British Council, Educational Pathways of Leaders: an international comparison, 2015.

Well, right off the bat, this one is going to be hard to validate. The British Council doesn’t really define “leadership” in an objective way and, in a footnote, also explained how:

“…For the most part, only leaders with higher education qualifications were considered for this study in order to determine how higher education contributes to professional success.”

It seems that University Canada is trying to prove that a university education uniquely builds leaders using a study that focused exclusively on university graduates. Which kind of defeats the purpose.

But let’s give them the benefit of the doubt and assume the people they’re studying are all genuine leaders. I guess that means the 55% whose professional qualities were formed by their liberal arts educations are the ones primarily responsible for the precipitous decline in institutional trust, economic crises, and general political chaos throughout so much of the world. Hardly a stirring recommendation.

To properly make their point, Universities Canada would have had to demonstrate that their graduates were indeed leaders and that their leadership had been a force for good. They didn’t.

“Between March 2012 and March 2022, 2,169,700 new jobs were created for university graduates, three times as many as those created for graduates of all other types of post secondary education combined.”

I won’t deny that a solid university education can open doors to important career advancement. In fact, I’m sure that many of the better job opportunities coming on line in fields like healthcare, engineering, and applied mathematics require degrees.

But industry trends suggest that things are changing. A recent Indeed study found that “67% of companies with 1,000 or more employees would consider doing away with the college requirement” with 26% of respondents reporting “that an applicant’s degree rarely matches the industry.”

A second study, The Emerging Degree Reset: How the Shift to Skills-Based Hiring Holds the Keys to Growing the U.S. Workforce at a Time of Talent Shortage found that “Some 46% of middle-skill and 31% of high-skill occupations experienced material degree resets between 2017 and 2019”

All of which indicates that the value of a university degree won’t completely disappear any time soon, but that it is in steady decline.

“As a $40 billion enterprise in direct expenditures, universities are significant drivers of economic prosperity. They provide employment for close to 410,000 people. Source: Statistics Canada, Financial Information of Universities and Colleges Survey 2019/2020, and Universities Canada survey on employment 2021.”

That claim isn't so simple. After all, the money didn't just magically appear out of nowhere. Most of it came from taxpayers and much of the rest from the pockets of students and their families. While money spent on university salaries and vendors does feed what economists call the multiplier effect, those benefits must be weighed against the serious costs born by other parts of the economy.

If, for example, taxpayers would have been able to spend some or all of those funds themselves, their choices might have led to a higher multiplier effect than university spending. Similarly, students and families could have avoided the heavy opportunity costs associated with an expensive education and, instead, invested the funds in ways that generated greater and more sustained economic activity.

We must also consider the debt burden created by all those billions of dollars of spending. Both governments and families borrow money to cover education costs: servicing those debts will be an ongoing responsibility that shouldn't be ignored.

So while at least some public support and student investment in post secondary education is reasonable, it’s wrong to claim that every penny spent “drives economic prosperity” for society as a whole.

Did Universities Canada successfully argue their case for investing your time and money in their product? If they were my students, I’d probably give them a C-minus.

As you gently note there is reason to think that a university degree can actually be a drag on the economy given the cost to taxpayers and families and, the not so good wages for some degrees.

It wii take a long time to undo the narrative of a U degree is the ticket to a comfortable life. In the meantime young people graduate with debt loads which hurts the economy

Canada, and many other countries, made a huge mistake using debatable data two decades ago that a university education promised higher incomes and therefore students should be charged more. The decision to 'charge what the degree was worth' had a number of delusory effects: first, created eye watering levels of student debt that made it more difficult for graduates to make decisions personal and professional unfettered by economic considerations, second, pressured students to make life altering education decisions almost immediately upon entering university by not giving them the financial space to seek out esoteric paths, and, third, reduced the opportunity for lower income students to go to university that often impacted the younger children in a family and most definitely women. It also had a negative impact on the less obvious economically rewarding subjects like philosophy, history, and english all of which have seen student enrolments fall, PhDs in those areas not hired, and departments shrunk. These trends have all added up, particularly in the United States, to reducing equality of opportunity and upward social mobility. While I can understand why universities might want to play loose with the data, they would do better to make the case that post-secondary education should be funded by the society as a key pillar of social mobility as well as advocating for expanded opportunities in the trades.