Does Increased Public School Funding Lead to Improved Educational Outcomes?

No matter how hard we try, life never works out quite perfectly. And it’s in the complex and often chaotic world of K-12 education where this might be most obvious. I spent twenty years of my own life teaching high school and I can tell you it’s hard to get right.

One narrative heard often from inside the education industry blames all problems on lack of sufficient funding. On average, as it turns out, governments in developed nations already spend more than 22% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on their children’s education.

My gut tells me that the sudden introduction of unlimited funding might not live up to expectations. But no one should rely on my gut feelings. Instead, I’m going to use some publicly available data from the US and around the world to see if it can’t give us a glimpse of what works and what doesn’t.

Of course, I can’t guarantee that my interpretations of that data are objectively correct. Just because there seem to be striking relationships between data points doesn’t itself prove the truth of a given insight. Correlation, as you’ve no doubt heard, isn’t the same as causation. But an unproven insight that’s nevertheless compelling sure beats complete ignorance.

At any rate, as we’ll soon see, it turns out that the actual amount that’s spent matters less than how it’s spent. But I’m getting way ahead of myself.

Choosing metrics

Before looking for the right data to illuminate a topic, you need clear target metrics. In our case, what kind of data is likely to best represent student outcomes and government school funding levels? Once we’re clear about what we’re looking for we can head out to see if such data is available.

Measuring outcomes

What best describes “success” in the context of education?

I don’t think employment or income rates - even when focused on recent graduates - are useful: there are simply too many other macroeconomic and social factors at play. So attributing employment and income trends to any one particular educational funding variable would be nearly impossible.

What about college enrolment or graduation rates? It’s true that the products of a successful college-focused K-12 education will be better prepared for the challenges of higher education. But that would ignore the large non-college-bound segment of the student population, wouldn’t it? Perhaps a K-12 system that narrowly optimizes its curriculum for college success has failed to serve a major segment of its population. Which suggests that college success is a weak proxy for K-12 operations.

Using data measuring proficiency in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills would similarly be too narrow. As important and profitable as STEM careers can be, they don’t come close to representing an educational system as a whole.

On the other hand, measuring literacy and numeracy (the ability to read and perform simple math) would be a meaningful metric but, considering how those basic skills are nearly universal across developed nations, they wouldn’t be helpful from the perspective of comparing outcomes.

So I guess that leaves the results of regular standardized testing of core educational skills. Sure, such tests are imperfect and there is always the risk that their existence can impact the very system they’re trying to measure. But they have both their advocates and unique charms. And they’re all we’ve got.

Specifically, we’ll be using two sets of testing metrics:

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), an assessment managed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA regularly measures 15-year-old students from all 38 OECD countries for proficiency in life skills related to three areas: reading, mathematics, and science. Note that the data we’ll be using, since it predates Costa Rica’s membership, covers only 37 countries.

For comparing US states, we’ll be using data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) which is administered by the US government’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). You can access this data on the nationsreportcard.gov website.

Measuring funding levels

The numbers covering economic and educational spending among OECD countries that I’ll be using here come through the US government’s NCES. Their original source was also the OECD itself. And the detailed education budget data broken by US states that we’re going to use are based US census data.

With that we’re about ready to start looking at our numbers.

One quick snapshot

In absolute terms, the US ranks fourth among 37 OECD nations for per-child spending. As of 2017, they spent $13,511 for each K-12 student. Luxembourg was number one by a mile: shelling out $21,244 for each and every wee little Luxembourger.

In that context, educational outcomes for US children don’t seem to match the investment. OECD PISA score data (from 2018) shows us that the US ranks 9th in reading scores for 15-year-olds, 13th in science, and 31st in math. Estonia, in that year, ranked first in both reading and science, and Japan won for math. The return on the US investment for those $13,511 seems weak.

Considering the size of the US economy and how much money its government spends in general, that investment number could be misleading. So bear in mind that, when measured as a percentage of its per capita gross domestic product, the US public school education spending comes in at 21 out of 37. Korea wins this round, devoting nearly 31% of its GDP to education. The US figure is 22.5%.

Luxembourg, by the way, seems to get even less bang for their buck. Despite the $21k they spend per-child, their PISA scores left them in 29th spot for reading, 27th for math, and 28th for science.

At the other end, when you think about Estonia’s stellar academic performance you might be surprised to learn that their per-student spending ($7,462) ranks 28th among 37 OECD countries. Even taking into account GDP, Estonia’s spending as a percentage of per capita GDP (nearly 22%) trails 23 other countries. Sharp investors, those Estonians.

One might be tempted to suggest that when it comes to education, funding has very little to do with performance.

The bigger picture

It’s time to dive into the data sets we’ve chosen and we’ll begin by comparing spending and performance among all 37 OECD countries.

By country

There are two ways to think about dollar amounts when they’re spread across multiple countries. There’s the raw dollar amounts, and the amount calculated as a percentage of each country’s gross domestic product. I will suggest that working with percentages will give us more accurate comparisons.

Why? A dollar spent in, say, Columbia isn’t quite the same as that same dollar being spent in the US. For one thing, a single dollar in Columbia should go a lot further: construction and maintenance costs are lower, as are teachers’ salaries. But it would also be unreasonable to expect Columbian governments to be in a position to lay out amounts for education that are competitive internationally.

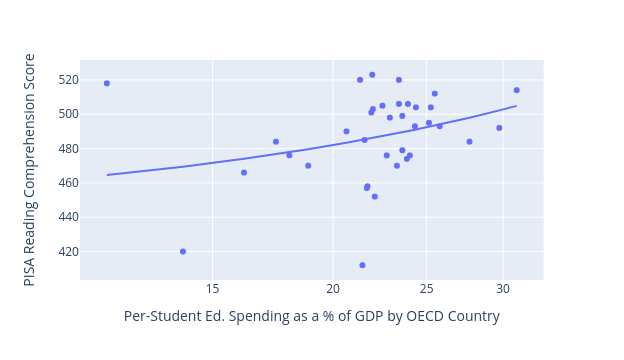

So the x-axis in the scatter plot shown in figure 1 represents per-student educational spending as a percentage of each country’s GDP. The further to the right a country’s dot appears on the chart, the greater is the proportion of their economy that’s devoted to education. The y-axis represents each country’s average PISA reading scores. The higher up on the axis a dot appears, the higher was their score.

The trend line shows a correlation between increased budgets and better scores. In other words, students in most countries that spend more do perform measurably better. But there are some noticeable dots that appear to buck the general trend - known as outliers.

Note, in particular, the lonely dot at the top-left of the chart representing Ireland. Their score (518) is much higher than you’d expect considering how little they spend on education (only 11.66% of their GDP). If I wrote before that the Estonians were great investors, the real payoff-for-investment-dollar trophy has got to go to Ireland.

The two low-score countries at or below the 420 mark are Mexico and Columbia. As with all outliers, it would be nice to dig a bit deeper to see if there aren’t some extraneous explanations for the unexpected results. Anyone reading this willing to share an insight?

Scatter plots using the PISA mathematics and science scores show similar relationships. You can generate those charts for yourself by downloading and running the code and data files hosted in my GitHub repository. As an added bonus, you’ll be able to hover your mouse over individual dots to display the country and data numbers they represent.

By US state

The United States isn’t called “United States” for nothing (except, at times, for the “United” part). To a large degree, each of the fifty states and that make up the union maintains its own distinct legal and economic environment. It’s hardly surprising, therefore, that we find that how - and how much - money is spent on education varies from state to state.

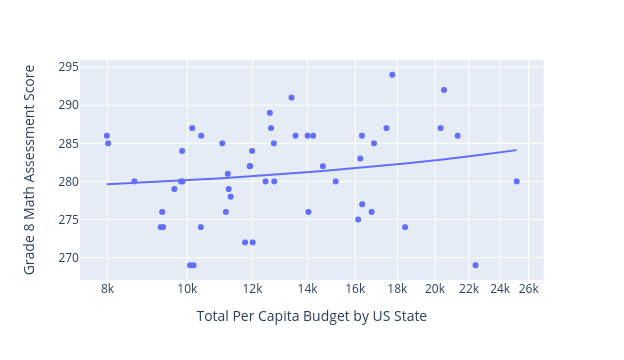

Figure 2 shows us each state’s total per-student budget and you can see how different they can be. Idaho, on the far left, spent just $7,985, while New York, on the far right, more than tripled Idaho, spending a whopping $25,139. Notably, Idaho’s students averaged a score of 286 on their grade eight math assessment, as compared to New York’s rather disappointing 280.

The next wealthiest school system behind New York’s is in the District of Columbia (DC). They spent more than $22,000 but also recorded the worst score in the entire country (269 - tied with the less generous states of Alabama and New Mexico). We’ll try to understand what’s going wrong with the heavy spenders in just a moment.

First though, the trend line in the graph tells us that, in the big picture, increased education budgets at the US state level do predict modest outcome improvements. But they are very modest: the R^2 value of this trend line is around 0.0288. Compare that with the far more dramatic R^2 from the PISA reading score graph we saw earlier (0.0941).

What’s going on here? Why do education investments in the US seem to have little or no impact on student outcomes?

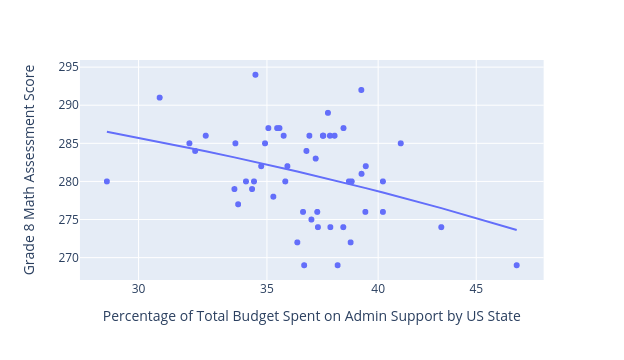

I think part of the answer may lie in figure 3. Take a look at that violently downward slope of the trend line.

As you can see from the caption, that figure shows us how US states spend their education budgets. In particular, it breaks out the non-classroom spending on administration and support services as a percentage of total spending. In other words. states whose dots appear further to the right devote a greater proportion of their budgets to support, and less to classroom instruction (i.e., teachers).

Our old friend, the District of Columbia is closest to the chart’s right edge, earmarking a mind numbing 47.24% of their funding to support. What do their students get out of it? That national worst score of 269. Alaska, that spends the second highest percentage on support, also scores low despite (or because of?) their administration-friendly choices (43.15%, to be precise).

There’s a crystal clear negative correlation here. A proper in-depth study would try to find out exactly what those administration funds were paying for. We would then look for patterns across states and even countries. But one thing that already seems clear, is that the way education funding is spent makes at least as much of a difference as how much of it there is.

That’s worth thinking about.