Does Immigration Drive Up Canadian Housing Prices?

The Free Press recently published a fascinating article claiming that immigration is not a significant cause of housing cost increases in the U.S. I’m not sure I’m completely convinced by their arguments, but the piece immediately got me wondering about Canada. Is there a meaningful relationship between the massive waves of immigration we’ve experienced and our own skyrocketing housing costs?

Fortunately, there are two Statistics Canada datasets that will be particularly helpful here: the shelter costs component of the Consumer Price Index and immigration numbers from the components of population change table. Unlike the U.S., we do have government data tracking where immigrants settle.

Those two tables provide overlapping data for 16 large municipal areas. Since most immigrants (92 percent of them in 2022/2023) settle in census metropolitan areas, those are obviously the regions on which we should focus.

One problem with the immigration data in its original form is that it gives us raw immigrant numbers for each city. This could potentially distort our results if, for example, a massive city like Toronto attracted only twice as many immigrants as the relatively tiny Charlottetown. To overcome that, I converted the immigration numbers to a proportional amount (per 1,000 total residents).

I then calculated the statistical relationship between immigration numbers and shelter costs using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is a number between -1 and 1 that tells us how strongly two things are connected. 1 means a perfect positive relationship: when one thing goes up, the other always goes up too. -1 means a perfect negative relationship: when one thing goes up, the other always goes down. 0 means no relationship: the two things don't seem to affect each other at all. A higher number (either closer to 1 or -1) means they move more predictably with each other.

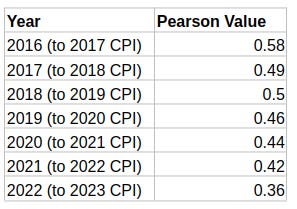

Here are the year-by-year results I got:

Bearing in mind that our data sample is smaller than we’d prefer, those do suggest a fairly strong correlation. Of course, that doesn’t prove that higher immigration levels are necessarily causing price increases. There may be other structural inputs at work here. But it is in important piece of evidence. And I think we can be confident ruling out the reverse: immigrants certainly aren’t actively attracted to cities by their higher costs!

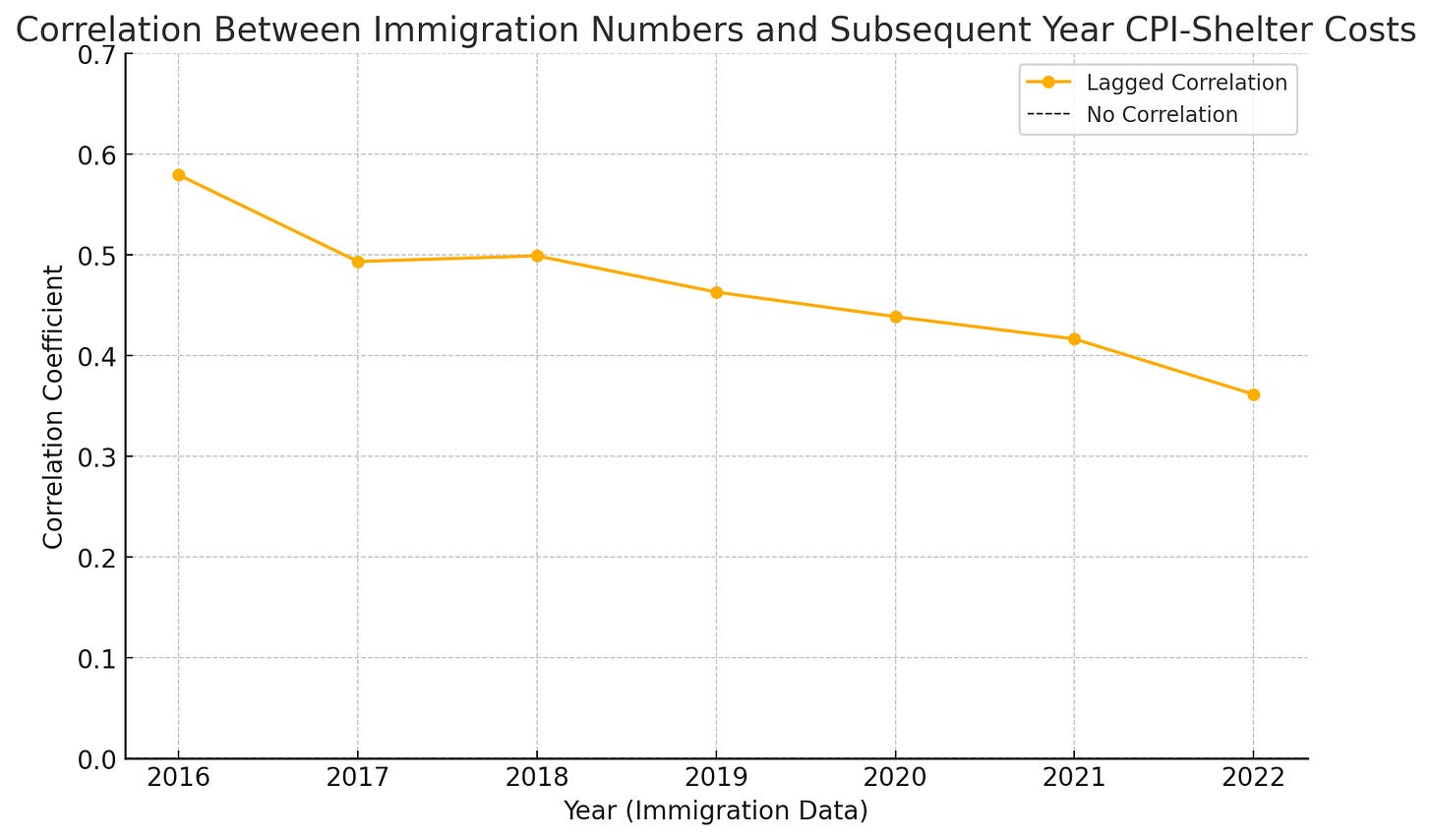

I also considered the possibility that the full impact of immigration might not be felt right away. Perhaps it takes a few months for housing markets to adapt to new demographic conditions. So I ran the Pearson calculations again, this time comparing, say, 2016 immigration numbers with 2017 shelter costs. The results showed a slightly stronger correlation:

Here are those numbers mapped over time:

You can clearly see the correlation has been gradually dropping. Why might that be happening? Here are a few possibilities:

Recent inflationary trends, including rising interest rates and construction costs, might have influenced CPI-shelter costs independently of immigration.

Housing supply in 2016-2018 may have been more elastic, with CPI-shelter costs responding more directly to changes in demand from immigration. As housing markets become more inelastic, supply constraints might be limiting price responsiveness to changes in demand.

Increased housing development initiatives, rent control policies, and zoning reforms in some cities might have moderated the impact of immigration on shelter costs. At the same time, delays in approvals for housing developments could have made the lag effect longer than one year, obscuring shorter-term correlations.

In the end, I think the premise that recent immigration surges have been at least partially responsible for driving housing costs upwards has not been proved, but it’s certainly a reasonable assumption. Which is one more data point demonstrating that, as valuable as controlled immigration can be, it can’t be overdone.

Have you considered the impact of former residents moving out because of (a difficult thing to know or quantify) the influx of migrants? That could effectively be displacing the overall effect of rising housing costs to outlying areas that you're not looking at.

Also, have you considered that mass migration to these areas might make them less desirable places for native Canadians to live (what we, in the US, used to call 'white flight' when blacks began moving into white neighborhoods)?

Both of these factors might have a negative impact on shelter costs which would make the strong correlation you've already established even more profound.

My question is this data directed at Canada as a whole? Or if you target it to Toronto or Vancouver (where the population has had an immigration surge) does your conclusion change?