Do Your Political Donations Make Any Real Difference?

Looking at 20 years of federal election campaign spending

Is it just me, or do I detect the sweet fragrance of a federal election in the air? Well never mind me, I have a terrible sense of smell either way. But just in case Decision Day is approaching, I thought I’d offer some context-enriched electoral numbers.

Analysis of the recent Toronto-St. Paul’s byelection shows a significant disconnect between campaign spending and positive outcomes. But that was just one election in one riding.

I’m going to explore some historical Elections Canada political donation data to see if the gifts Canadians give their political parties have much of an impact on the way you and I actually vote. The donations dataset I used covers the years since January 2004 and comprises more than 5.8 million individual donations.

For our purposes, the data itself identifies donations by amount, donor category (individual, corporation, association, trade union, etc.), and the recipient political party. It also contains donor names and addresses - but those don’t interest me right now.

The first thing you’ll notice about the Canadian data is how differently elections work here when compared to the U.S. - and that’s something of which we should definitely be proud. Through the seven federal elections since 2004, the average total of all combined donations to the four largest parties was around $66 million. That’s $1.63 per Canadian.

Now compare that with the $15.9 billion thought to have been wastedspent on all federal elections (President, Congress, Senate) in the 2024 U.S. election cycle. That translates to $47.89 for every American.

Think Canadian political parties are dominated by big-business? Well here’s something to chew on: 98.6 percent of the value of all political donations since 2004 - $1.18 billion in all - came from individuals. Only 1.39 percent were from corporations. And 75 percent of all donations were for $133 or less.

That’s the big picture. But what I’m really hoping to find is some indication that funding actually makes a difference in the polling booth. Do parties that raise more money tend to receive more votes and win more seats?

Of course discovering such a relationship might not be that useful. After all, perhaps it’s not that money (and the advertising and campaign logistics that money can buy) delivers more votes. Isn’t it also possible that popular parties attract more donors who were planning to vote that way even before seeing the ads?

We’re also going to have to keep in mind a whole galaxy of confounding variables. Some parties, for instance, might simply run better campaigns that accomplish more with less money. Similarly, some elections can be largely decided on economic or social issues that can’t be drowned out by all the money and clever Twitter videos in the world.

To address my questions, I identified three sets of numbers:

Total donation amounts directed to each of the four largest parties during the calendar years within which each of the seven most recent federal elections took place

Seat totals by party from each of those elections

Vote totals by party from each of those elections

Then, on the assumption that parties tend to spend all the donations they receive, I compared campaign spending amounts to both seat and vote counts. Are there meaningful statistical relationships between higher spending and better outcomes?

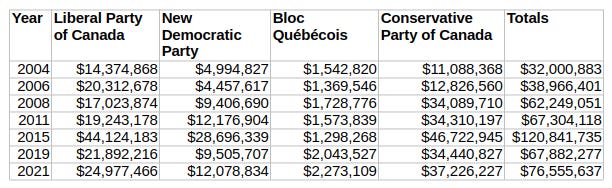

First though, here are the overall numbers:

The Bloc obviously benefits from their exclusive focus on Quebec. Since they don’t need to spend money campaigning outside their province, the seats they do win come a lot cheaper.

The disparity between the NDP’s extremely high per seat spending and its low per vote costs comes down to the peculiarity of our first-past-the-post electoral system. Their many second and third-place finishes give them loads of votes that don’t translate to actual seats.

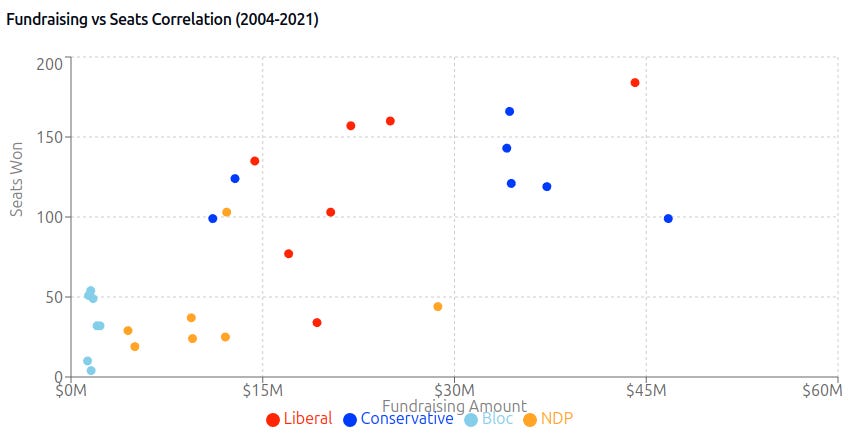

Now here’s how the relationship between campaign spending and successfully winning seats looks:

Ideally, you like your party to hit points as far to the left (low spending) and the top (lots of seats) of the graph as possible. No party seems to have cracked that mystery - at least through the years since 2004.

That could suggest the possibility that heavy campaign spending is the only reliable way to win elections. However, were that actually true, the visual relationship between factors in this chart is not nearly as straight (linear) as we’d expect.

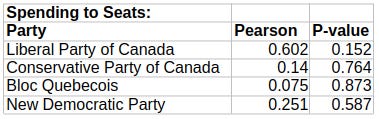

In fact, calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient and P-values for those datasets tells us that there’s no obvious statistically meaningful relationship between spending and electoral success. Here are actual numbers:

The only result that came even close to significant was the relationship between Liberal spending and votes:

However since vote totals don’t win elections in Canada, that’s not such a useful piece of information.

So from a purely technical perspective, you might say we’re seeing the best possible outcome: there doesn’t seem to be any statistical relationship between campaign spending and electoral victory. Which I guess means there’s no compelling argument for donating to your favorite party.

"Think Canadian political parties are dominated by big-business?"

I world be GREATLY surprised if they were, though perhaps not for the reason that you imply. I don't think that Canada HAS any 'big business', at least not by the standards down here. In fact, despite their much higher taxes than the US, I'm pretty sure even without checking that we have individual US States, even individual companies, with higher annual revenue than the entire annual revenue of the Canadian government.

No offense intended to our northern neighbors, but US elections are generally for much higher stakes with a much greater difference in likely policy outcomes depending on which of our parties win and with a much richer (on average) population and corporate sector to engage in donations and other election-related activities. It would be more counterintuitive if US elections were NOT receiving much more money and a much higher percentage of corporate involvement.

Thanks for crunching the numbers. I fear our neighbours to the South went sideways when they passed a law declaring corporations are ‘persons’, thereby allowing them to donate huge amounts to election campaigns.