Bad Research Still Costs Good Money

I have my opinions about which academic research is worth funding with public money and which isn’t. I also understand if you couldn’t care less about what I think. But I expect we’ll all share similar feelings about research that’s actually been retracted by the academic journals where it was published.

Globally, millions of academic papers are published each year. Many - perhaps most - were funded by universities, charitable organizations, or governments. It’s estimated that hundreds of thousands of those papers contain serious errors, irreproducible results, or straight-up plagiarized or false content.

Not only are those papers useless, but they clog up the system and slow down the real business of science. Keeping up with the serious literature coming out in your field is hard enough, but when genuine breakthroughs are buried under thick layers of trash, there’s no hope.

Society doesn’t need those papers and taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay for their creation. The trick, however, is figuring out how to identify likely trash before we approve a grant proposal.

I just discovered a fantastic tool that can help. The good people behind the Retraction Watch site also provide a large dataset currently containing full descriptions and metadata for more than 60,000 retracted papers. The records include publication authors, titles, and subjects; reasons for the retractions; and any institutions with which the papers were associated.

Using that information, I can tell you that 798 of those 60,000 papers have an obvious Canadian connection. Around half of those papers were retracted in the last five years - so the dataset is still timely.

There’s no single Canadian institution that’s responsible for a disproportionate number of clunkers. The data contains papers associated with 168 Canadian university faculties and 400 hospital departments. University of Toronto overall has 26 references, University of British Columbia has 18, and McMaster and University of Ottawa both have nine. Research associated with various departments of Toronto’s Sick Children’s Hospital combined account for 27 retractions.

To be sure, just because your paper shows up on the list doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong. For example, while 20 of the retractions were from the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, those were all pulled because they were out of date. That’s perfectly reasonable.

I focused on Canadian retractions identified by designations like Falsification (38 papers), Plagiarism (41), Results Not Reproducible (21), and Unreliable (130). It’s worth noting that some of those papers could have been flagged for more than one issue.

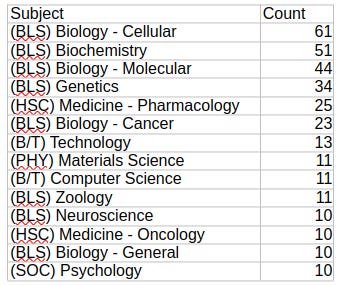

Of the 798 Canadian retractions, 218 were flagged for issues of serious concern. Here are the subjects that have been the heaviest targets for concerns about quality:

You many have noticed that the total of those counts comes to far more than 218. That’s because many papers touch on multiple topics.

For those of you keeping track at home, there were 1,263 individual authors involved in those 218 questionable papers. None of them had more than five such papers and only a very small handful showed up in four or five cases. Although there would likely be value in looking a bit more closely at their publishing histories.

This is just about as deep as I’m going to dig into this data right now. But the papers I’ve identified are probably just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to lousy (and expensive) research. So we’ve got an interest in identifying potentially problematic disciplines or institutions. And, thanks to Retraction Watch, we now have the tools.

Kyle Briggs over at CanInnovate has been thinking and writing about these issues for years. He suggests that stemming the crippling flow of bad research will require a serious realigning of the incentives that currently power the academic world.

That, according to Briggs, is most likely to happen by forcing funding agencies to enforce open data requirements - and that includes providing access to the programming code used by the original researchers. It’ll also be critical to truly open up access to researchers to allow meaningful crowd-sourced review.

Those would be excellent first steps.

Probably worth noting that in the field of climate research governments have been actively encouraging faulty research and actively tamping down any complaints to it. We need to take the ideology out of the funding as well as the financial incentives.